The year 1609 marked a pivotal moment in the history of astronomy, as two visionary men made groundbreaking observations that would alter the course of scientific discovery. While the name Galileo Galilei is forever etched in the annals of history, it is a lesser-known figure—Thomas Harriot—whose contribution to the exploration of the Moon would remain obscured for centuries. This article revisits these early pioneers of lunar exploration, their contrasting paths, and the tools that helped shape our understanding of the heavens.

A Pioneering Moment in Lunar Exploration

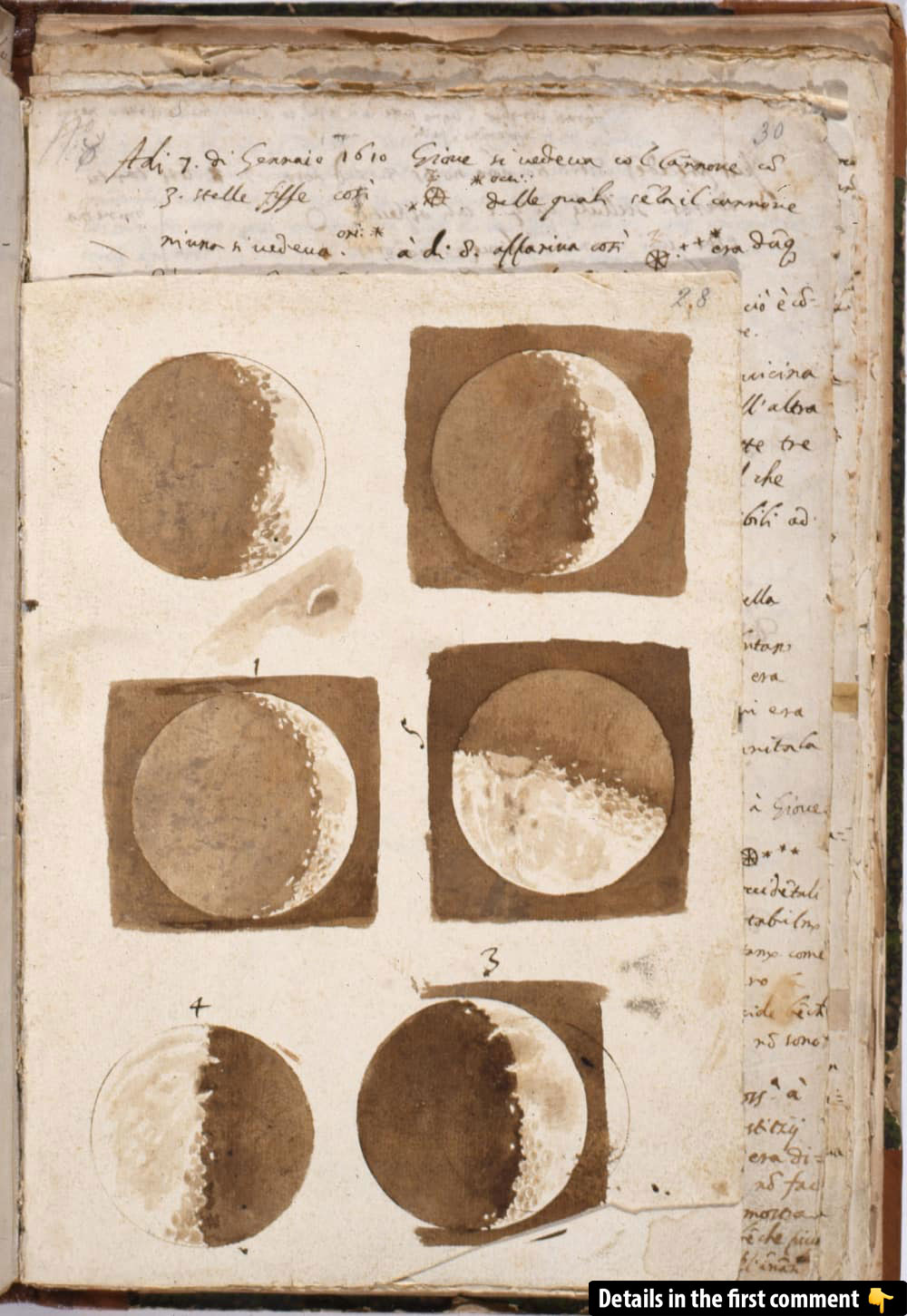

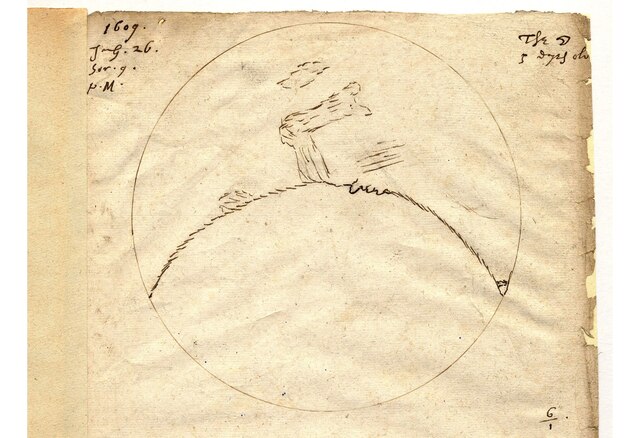

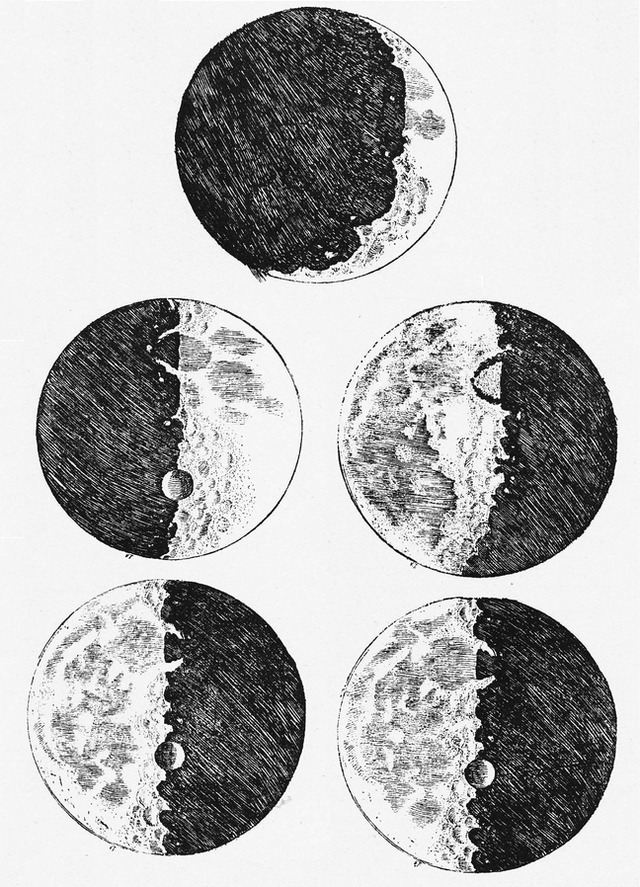

On July 26, 1609, in the quiet suburbs of Kew, West London, a mathematician and astronomer named Thomas Harriot etched the first known drawing of the Moon through a telescope. The drawing, though crude by modern standards, marked the beginning of an epic journey of celestial discovery. Harriot’s sketches preceded those of the more famous Galileo Galilei by several months, yet it was Galileo’s name that became synonymous with lunar observation, partly due to the way he popularized the telescope’s potential.

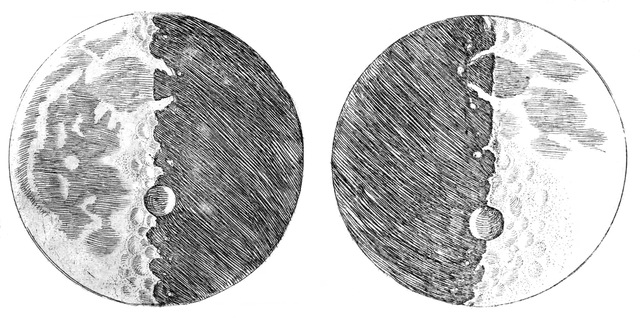

Harriot’s drawing, while simple, revealed the lunar surface’s dark patches and seas of solidified lava, what we now recognize as lunar maria. Though it would take centuries for his contributions to be fully acknowledged, Harriot’s pioneering spirit in using the telescope would lay the foundation for future astronomical advancements.

Video

Watch the video to see how Galileo changed the universe forever. His groundbreaking discoveries reshaped our understanding of the cosmos!

Thomas Harriot: The Forgotten Pioneer

Thomas Harriot was a man of many talents. A mathematician, astronomer, and linguist, he was also a member of the intellectual circle surrounding the Earl of Northumberland, one of the wealthiest men in England at the time. Harriot’s early lunar observations were facilitated by a Dutch-made telescope with a six-times magnification, less powerful than what we are accustomed to today, but a tool of immense importance in the early 17th century.

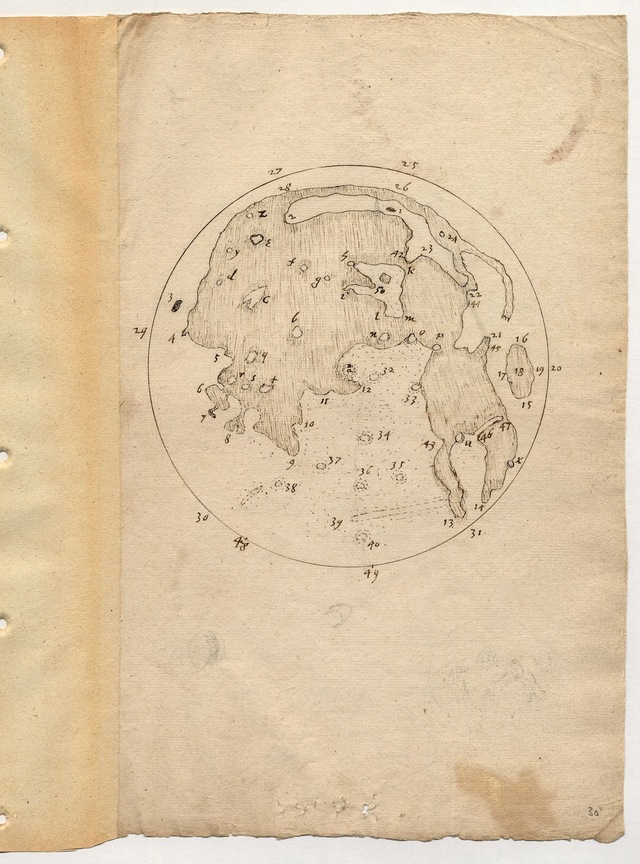

The significance of Harriot’s drawings lies not just in their timing but in their content. His observations of the Moon were some of the first to reveal the Moon as a rugged, relief-filled body, similar to Earth. His sketches also depicted what were likely the Mare Crisium, Mare Tranquillitatis, and Mare Foecunditatis—the dark plains that would later become central to lunar studies. While Galileo would later build on these observations, Harriot’s contributions were overshadowed by his quieter, more secure life.

Harriot’s lack of ambition for public recognition stands in stark contrast to Galileo’s relentless pursuit of fame. Harriot, supported by a generous patronage from the Earl of Northumberland, did not require the acclaim of the scientific community, which is why his works remained largely unknown until much later. His work, grounded in correspondence rather than publication, was aimed more at personal advancement and academic collaboration than at fame.

Galileo Galilei: The Face of Lunar Discovery

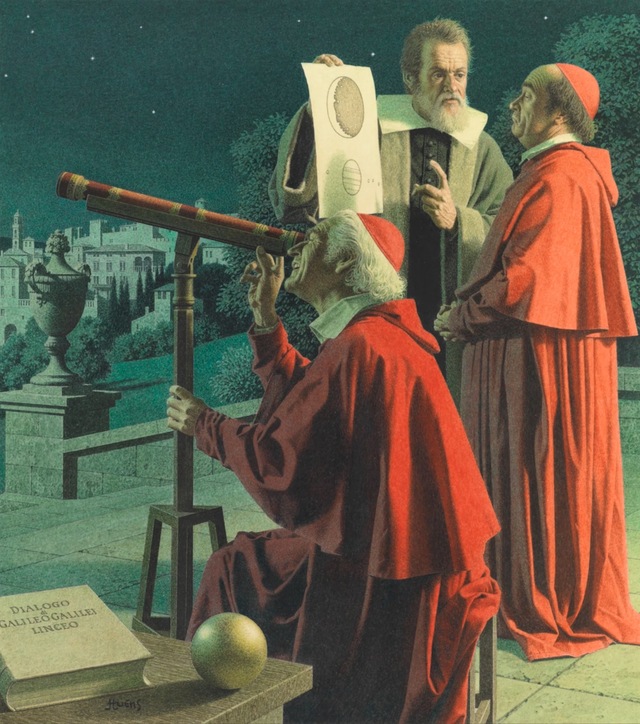

Galileo, on the other hand, was driven by a desire to challenge the status quo. After perfecting his own version of the telescope, he began making astronomical observations that would shake the foundations of scientific thought. In late 1609, Galileo turned his telescope towards the Moon, making his own series of drawings that would eventually earn him widespread recognition.

Galileo’s lunar observations differed from Harriot’s in that he saw the Moon not just as a celestial body but as an imperfect sphere, revealing mountains, valleys, and shadows that indicated the presence of craters. Galileo was the first to describe these features in detail, noting the behavior of shadows and their relationship to the lunar terrain. His observations were groundbreaking and changed the way people viewed not just the Moon but the entire universe.

In addition to his lunar discoveries, Galileo was the first to observe the moons of Jupiter, furthering the Copernican heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe. This caused an uproar in the Catholic Church, which still adhered to the geocentric model that placed Earth at the center. Galileo’s bold conclusions, along with his advocacy of the heliocentric theory, ultimately led to his trial for heresy in 1633. Unlike his contemporary Giordano Bruno, who was executed for similar beliefs, Galileo was placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life.

The Telescope: A Game-Changing Instrument

The telescope, the instrument that made these revolutionary discoveries possible, was a product of European innovation. Created by Hans Lippershey in the Netherlands in 1608, the telescope’s ability to magnify distant objects opened new possibilities for exploration. Both Harriot and Galileo used the device, though with varying degrees of sophistication. Harriot’s initial observations were made with a telescope that offered modest magnification, while Galileo’s design was far more powerful, allowing him to capture finer details.

The telescope quickly spread across Europe, becoming an essential tool for astronomers and scientists alike. Its impact was not only astronomical but also philosophical, challenging the prevailing worldview and leading to a reevaluation of humanity’s place in the cosmos.

Parallel Lives: Harriot and Galileo’s Diverging Paths

Though Harriot and Galileo shared similar interests and made concurrent discoveries, their lives took very different paths. Harriot, with his patronage and secure position in English society, led a life of comfort and relative obscurity. He never sought the spotlight, content to share his findings in private circles. In contrast, Galileo’s outspoken nature and his willingness to challenge authority led to both acclaim and controversy. His work would be instrumental in shaping modern science, but not without personal cost.

Both men observed the moons of Jupiter, and both noted sunspots independently. However, it was Galileo who famously championed the Copernican model, a theory that suggested the Earth and other planets orbited the Sun. This idea was a direct challenge to the geocentric model supported by the Church, and Galileo’s outspoken support for it led to his eventual trial and house arrest.

The Church and Astronomy: A Struggle for Truth

The religious and political climate of 17th-century Europe played a crucial role in the careers of both Harriot and Galileo. The Catholic Church, which held considerable power during this time, saw the heliocentric theory as a direct challenge to its teachings. Galileo’s support for Copernicus’s model led to widespread conflict, culminating in his trial for heresy.

Harriot, however, did not face the same persecution. His work, though groundbreaking, remained largely unpublished, and his private life allowed him to avoid the religious and intellectual conflict that Galileo faced. The difference in their public reception highlights the intersection of science, religion, and politics during the Scientific Revolution.

Conclusion: A Shared Legacy of Discovery

While Galileo’s name is forever tied to the history of lunar exploration and modern science, Thomas Harriot’s contributions should not be overlooked. Both men, working independently and within different contexts, made critical observations that advanced our understanding of the Moon and the universe. Their discoveries laid the groundwork for the space exploration we take for granted today.

In reflecting on their lives, it becomes clear that the pursuit of knowledge is not always driven by fame or recognition. Both Harriot and Galileo sought to understand the world around them, driven by curiosity and the desire to uncover truth. In the end, their combined efforts represent the first steps in a long journey of exploration—one that continues to this day, as humanity looks to the stars for answers.

Video

Check out the video to learn how Galileo unlocked the doors to the universe. His revolutionary discoveries opened up a new era of scientific exploration!