Hatshepsut, one of ancient Egypt’s most fascinating rulers, broke centuries of tradition by ascending to the throne as a female pharaoh. In a world dominated by male leadership, her reign stands as a testament to both her political savvy and her ability to navigate the complex cultural norms of her time. Among the many artifacts that offer a glimpse into her power, a life-sized granite statue reveals her unique approach to kingship, blending feminine grace with masculine symbolism. This statue, a remarkable representation of Hatshepsut, continues to captivate historians and art enthusiasts alike, shedding light on the enduring legacy of one of Egypt’s most formidable rulers.

The Statue of Hatshepsut: A Dual Representation

One of the most iconic representations of Hatshepsut is a granite statue, which shows her seated, wearing the nemes headdress, a symbol reserved for the reigning king. The choice of this headdress, traditionally worn by male pharaohs, is not just a stylistic choice but a powerful symbol of her authority. Hatshepsut’s attire reflects her identity as a woman, yet her titles, inscribed alongside her statue, already reference her throne name “Ma’at-Ka-Re,” placing her firmly within the realm of kingship. Interestingly, while the inscriptions carry masculine connotations, such as referencing her as the “Lady of the Two Lands” and the “Bodily Daughter of Re,” her titles remain distinctly feminine, highlighting the delicate balance she maintained between her womanhood and royal status.

The statue reveals not just Hatshepsut’s regal identity but also her diplomatic approach to power. Despite defying conventional gender roles, Hatshepsut did not attempt to hide her femininity. Instead, she seamlessly blended it with male iconography to reinforce her legitimacy as a ruler. This delicate equilibrium between feminine grace and masculine symbolism reflects her desire to assert both her unique identity as a woman and her unassailable role as pharaoh of Egypt.

Video

The Mysterious Scene on the Back of the Throne

On the back of the throne of the statue is a partially preserved scene that has puzzled many scholars. The imagery seems to depict two goddesses standing back-to-back, one of which has the body of a pregnant hippopotamus, feline legs, and a crocodile’s tail—reminiscent of Taweret, the protector of women and children. However, this figure is likely to represent Ipi, a divine protector of royalty. Ipi appears in similar poses on other royal statues, such as those from the 17th Dynasty. The presence of such a deity, possibly guarding Hatshepsut’s throne, reinforces the divine right that she claimed as ruler.

The depiction of these figures further exemplifies the blending of royal iconography and divine protection that was integral to Hatshepsut’s reign. By positioning these divine figures behind her, the statue not only asserts her power but also connects her rule to the gods themselves, affirming that she governed with divine approval and protection.

Hatshepsut’s Public and Private Representations

While Hatshepsut’s public iconography was designed to convey her as a king, many of her depictions adhered to long-established royal traditions. In public statues and monuments, she was portrayed as a youthful and vigorous male figure, embodying the ideal king. These representations were not attempts to deceive her subjects about her gender, but rather part of a longstanding tradition in which kingship was symbolized in male terms. This was especially true for the royal statues, such as colossal sphinxes, kneeling figures, and standing statues, all of which depicted her in a typically masculine manner.

Despite the masculinity of these depictions, there was a subtle continuity in her use of feminine titles. Her personal name, Hatshepsut, meaning “Foremost of Noble Women,” was consistently used, underscoring her connection to her female identity. This blending of male imagery with feminine titles was a strategic move to solidify her position while respecting traditional royal norms.

Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power and Her Role as Pharaoh

Hatshepsut’s ascent to the throne was as unprecedented as it was remarkable. Born as the daughter of King Thutmose I, she grew up in the royal court, married her half-brother Thutmose II, and later became the regent for her stepson, Thutmose III. Over time, she managed to assert her position and declared herself pharaoh in her own right. Unlike many of her predecessors, her rise to power was not purely a result of dynastic succession; instead, it reflected her strategic political maneuvering and her determination to secure her role.

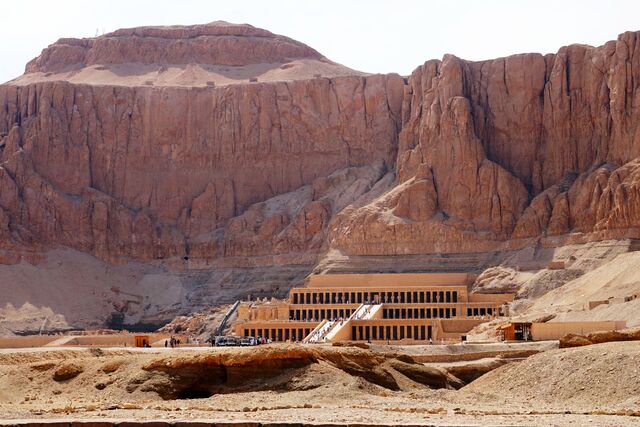

Her reign saw a remarkable period of peace, economic growth, and monumental construction projects, including the famous temple at Deir el-Bahari. Her decision to present herself as pharaoh, both in title and in public imagery, was a direct response to the political realities of her time, where the role of female rulers was not only rare but often seen as an anomaly. By taking on the iconography of a king, she reinforced her authority and legitimized her reign in the eyes of both her subjects and foreign powers.

Adopting Male Iconography to Solidify Authority

Hatshepsut’s decision to adopt male imagery was not only a political necessity but also a declaration of her intent to rule as an equal among the great pharaohs of Egypt. In doing so, she ensured that her reign would not be seen as an aberration but as a continuation of the divine kingship that had long been a part of Egypt’s political fabric. Her use of male imagery, including the traditional nemes headdress and the ceremonial beard, reinforced her role as a ruler, not just as a woman who happened to rule.

This bold choice also had strategic implications. By presenting herself as an idealized male king, she aligned herself with the most powerful and enduring symbol of Egyptian authority, allowing her to consolidate her power and prevent challenges to her rule. This wasn’t just a matter of artistic representation but a crucial element of her political strategy.

Discovery and Restoration of the Statue

The granite statue of Hatshepsut was uncovered in the early 1920s during excavations at her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari. The discovery was significant not only because of the statue’s monumental size but also because it reflected Hatshepsut’s role as one of Egypt’s greatest rulers. The torso of the statue had been discovered earlier in 1869, and the two fragments were finally reunited in 1998, allowing scholars to fully appreciate the grandeur of this exceptional representation.

The statue’s restoration and subsequent display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York provided new insights into Hatshepsut’s reign and her lasting legacy. The statue continues to stand as a powerful symbol of her defiance against tradition and her assertion of authority as pharaoh. For modern-day audiences, it serves as a testament to the strength and resilience of a woman who defied the norms of her time and ruled Egypt with wisdom and power.

Conclusion: Hatshepsut’s Enduring Influence

Hatshepsut’s reign was one of innovation and strength, characterized by her ability to navigate the complexities of gender and power. Through her adoption of male iconography and her strategic use of feminine titles, she crafted a legacy that both upheld traditional royal imagery and broke new ground for women in leadership. The granite statue of Hatshepsut, with its dual representation of femininity and masculinity, remains one of the most profound symbols of her reign. Today, as scholars and visitors continue to study her life and achievements, Hatshepsut’s legacy remains a powerful reminder of the transformative power of leadership, regardless of gender.

Video

Watch the documentary The Greatest Female Pharaoh: Hatshepsut to explore the remarkable story of one of ancient Egypt’s most legendary rulers.