In the bustling streets of medieval Novgorod, a young boy named Onfim unknowingly immortalized a moment of boredom on a piece of birch bark. His doodle, crafted over 800 years ago, features a horseback rider slaying an enemy, a striking self-portrait that gives us a rare glimpse into the imagination of a medieval child. This seemingly simple act of artistic rebellion opens a window into the world of early medieval art and offers a unique perspective on childhood, creativity, and the timeless act of doodling.

Onfim’s Self-Portrait: A Glimpse Into the Past

Onfim’s self-portrait, found on a fragment of birch bark, has become one of the most iconic examples of medieval doodling. Likely drawn around 1260, this image captures Onfim as a horseback rider, sword in hand, slaying a fallen enemy. While the style is crude, with exaggerated stick figures and minimal detail, the act of drawing itself speaks volumes. Onfim not only scrawled his name on the artwork, which includes his signature “ОНѲИМЄ,” but also left behind a visual narrative that reflects both his imagination and the time in which he lived.

Onfim’s drawing appears alongside exercises of the Cyrillic alphabet, suggesting that he may have been bored with his schooling, much like children today might doodle during long classroom sessions. The simplicity of the figures—round torsos, long legs, and exaggerated facial features—are consistent with what we might expect from a seven-year-old artist, providing a direct connection to the experience of childhood during the medieval period.

The presence of this doodle on birch bark is also significant. The material was commonly used before paper was widely available and was inscribed with metal or bone implements. This medium allowed for an enduring preservation of Onfim’s artwork, which, thanks to the wet, low-oxygen conditions of the soil in Novgorod, has remained intact for centuries. His self-portrait, though created for no grand purpose, has become a window into the past, offering insights into the playful imagination of a medieval child.

Video

Watch the video The Story of Onfim, a medieval child.

Onfim’s Influence and Legacy in Medieval Art

Onfim’s artistic contribution goes beyond the scope of a mere doodle. His works are among the earliest examples of child-produced art ever discovered, a fact that elevates his sketches to a significant place in the history of medieval art. The doodles are not just idle scribbles but represent a unique form of expression that offers insights into the mind of a child in the 13th century.

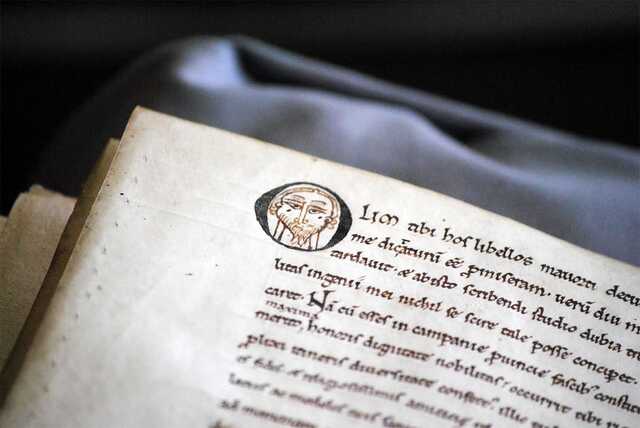

Moreover, Onfim’s decision to sign his name on his artwork was extraordinary for its time. While medieval art typically lacked signatures, Onfim’s name was proudly included, marking him as both the creator and the subject of his creation. This act of self-insertion into his work was radical, reflecting a level of individuality that was uncommon in medieval times. It hints at a budding sense of identity and ownership over one’s work, qualities that would become central to the Renaissance but were rare in the earlier medieval period.

The style of Onfim’s doodles—simple, direct, and often fantastical—also contrasts sharply with the more formal and religious art of the period. This shift in style highlights the diversity of artistic expression in medieval Novgorod and provides a glimpse of the less structured, more personal forms of creativity that existed alongside the monumental religious and political art of the time.

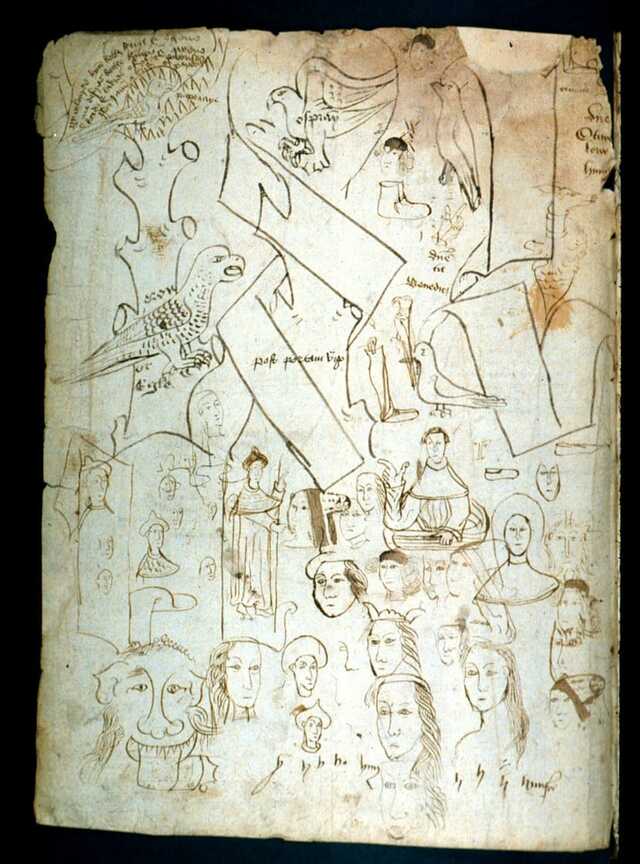

Other Doodles from the Same Era: Exploring Medieval Scribbles

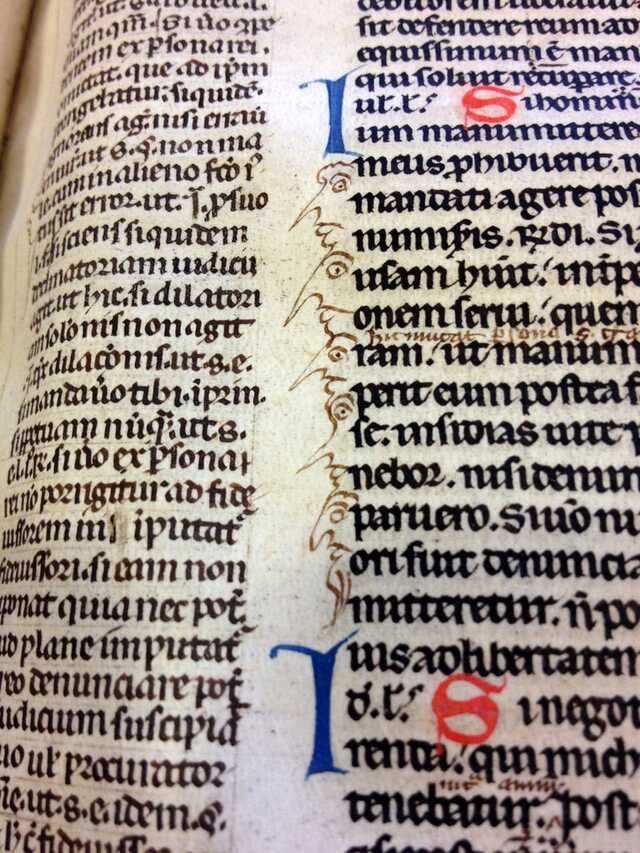

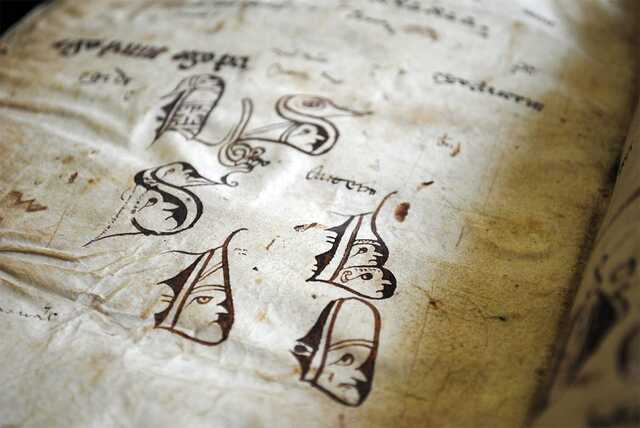

While Onfim’s doodle stands out due to its playful and imaginative nature, he was not alone in his artistic endeavors. Medieval scribes, whether bored or experimenting with their tools, often left behind sketches and doodles in the margins of manuscripts. These “pen trials” were typically drawn during moments of boredom or as a way to test the ink flow of their quills. These scribbles were typically simple and unrefined, but they provide valuable insight into the everyday life and thought processes of those who lived during the medieval period.

Erik Kwakkel, a medieval book historian, has conducted extensive research into these pen trials and medieval doodles. His work has uncovered a wide array of sketches from 13th and 14th-century manuscripts, many of which were drawn by scribes testing the ink flow or simply passing time. These pen trials range from geometric shapes to crude faces and even more complex figures. In some cases, these scribbles are accompanied by short sentences or words, written in the scribe’s native hand, further linking the doodles to personal identity and artistic expression.

Kwakkel’s research reveals that these sketches were not just idle pastimes but offered clues about the individuals who created them. Some doodles reflect the cultural and regional influences of the scribes, while others provide a glimpse into their personal lives. For example, a 13th-century doodle discovered in a manuscript containing Juvenal’s Satiresdepicts a smirking face, likely created by a bored student as a form of rebellion or distraction during their lessons.

These doodles, much like Onfim’s, speak to a shared experience of boredom and creativity across time, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries. Whether it’s Onfim drawing himself slaying an enemy or a 14th-century scribe sketching a smiley face, these seemingly insignificant doodles reflect the universal need for self-expression, even in the most mundane circumstances.

Comparative Analysis: Onfim’s Doodles vs. Other Medieval Art

When comparing Onfim’s self-portrait to other medieval doodles, several similarities and differences emerge. Like many other medieval scribes, Onfim utilized the materials available to him—birch bark in his case—creating a lasting mark on history. While other scribes left behind pen trials in the margins of important manuscripts, Onfim’s work was a more personal expression, with figures drawn out in dynamic, action-filled scenes.

Despite the differences in style and medium, both Onfim’s doodle and other pen trials share a commonality: they reflect the spontaneous, unfiltered creativity of individuals who were not necessarily artists by profession but still felt the urge to express themselves through drawing. These works, though created out of boredom or necessity, add depth to our understanding of the medieval world, showing that art was not always confined to the realms of religious or courtly patronage.

Video

Watch the video to discover why Yankee Doodle called it “macaroni.”

Conclusion: The Power of Doodles in Understanding the Past

Onfim’s self-portrait and the other medieval doodles discovered by historians like Erik Kwakkel are not just simple sketches. They are windows into the minds of individuals from a distant past, offering a glimpse of their daily lives, thoughts, and imaginations. Through these seemingly insignificant drawings, we can better understand the experiences of children, scribes, and individuals who lived in the medieval period.

The fact that these doodles have survived for centuries speaks to the enduring nature of human expression. Onfim’s name, etched on his artwork, represents more than just a signature; it’s a testament to the individuality and creativity that existed long before the Renaissance. These doodles, though simple, are profound in their ability to connect us with the past, reminding us that even in the most mundane moments, art and expression have always been integral to the human experience.