Fifty years ago, the world of anthropology was forever altered by the discovery of a fossil that would reshape our understanding of human origins. The fossil, known as “Lucy,” was a 3.2 million-year-old skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis, an early ancestor of modern humans. Found in the Afar region of Ethiopia by paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson in 1974, Lucy’s nearly complete skeleton provided scientists with unprecedented insights into our evolutionary past. This remarkable discovery not only revealed important details about early hominins but also challenged long-held assumptions about the path that led to Homo sapiens.

The Discovery of Lucy: A Pivotal Moment in Paleoanthropology

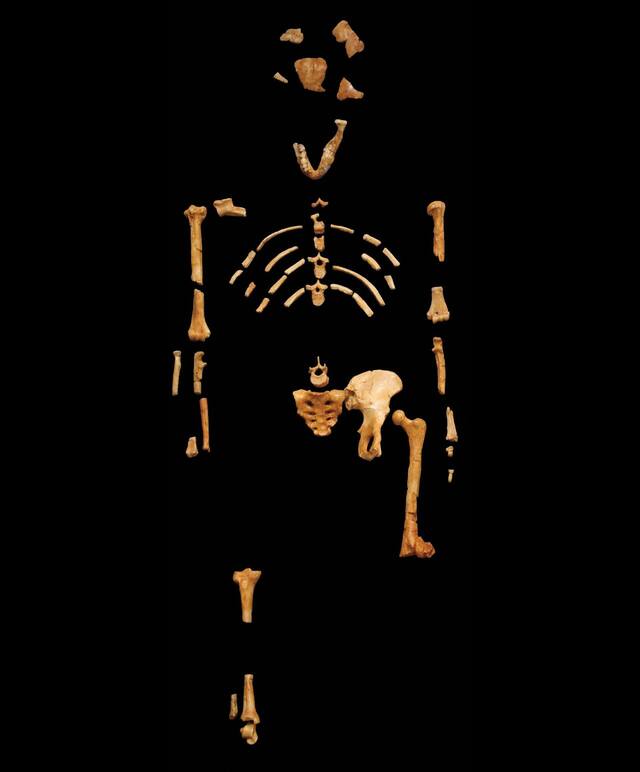

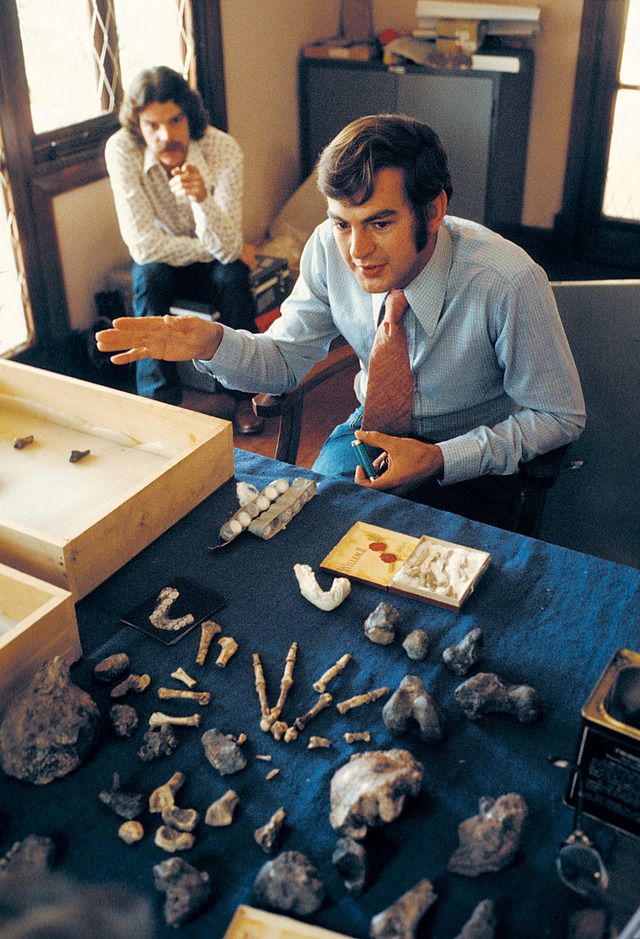

The search for human ancestors in East Africa was already underway when Johanson and his team arrived in the Afar region in the early 1970s. After months of careful excavation and following the discovery of a knee joint in 1973, the team made a breakthrough in November 1974. Johanson spotted a piece of bone in a hillside gully, which turned out to be part of Lucy’s skeleton. Over the course of several weeks, the team recovered 47 bones, representing over 40% of her body—a rare find for such ancient fossils.

Lucy was named after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which played during the team’s celebratory moments after the discovery. Her near-complete skeleton made her the most significant early hominin fossil to date. The implications of her discovery were far-reaching, as it was the first time a hominin with both apelike and humanlike traits had been found in such a well-preserved state.

Video

Watch the video Walking With Lucy from the California Academy of Sciences.

The Life of Lucy: Insights into the Behavior and Adaptations of A. afarensis

From Lucy’s skeleton, scientists were able to draw important conclusions about her life and her species. Standing only about 3.5 feet tall and weighing between 60 to 65 pounds, Lucy was much smaller than modern humans, resembling a young child in size. Despite her small stature, Lucy walked upright, a critical trait in the evolution of humans. Her pelvis, knee, and ankle bones indicated that she was bipedal, much like modern humans, though her arms and finger bones suggested she could still climb trees.

Lucy likely spent much of her time in the trees, foraging for food like fruits, leaves, and insects. However, her bipedalism indicates she also spent time on the ground, navigating the diverse ecosystems of Pliocene East Africa. Her diet was varied, and she likely relied on both plant material and small animals for sustenance.

Lucy’s Last Day: Theories About Her Death

The cause of Lucy’s death remains a subject of debate among scientists. Two theories have gained prominence. One possibility is that Lucy died due to a fall from a tree. Researchers have noted fractures on her skeleton, particularly in her shoulder and ribs, which could be consistent with a fall from a height. The impact would have caused significant trauma, particularly to her lower limbs and upper body.

The second theory suggests that Lucy may have been the victim of a predator attack. A carnivore tooth mark found on her pelvis suggests that a large predator, such as a crocodile or a big cat, may have bitten her around the time of her death. Given the dangers posed by large predators in her environment, this remains a plausible explanation for her untimely demise

Lucy and the Social Structure of Australopithecus afarensis

While much of Lucy’s daily life remains speculative, it is likely that she lived in a mixed-sex group, as suggested by other fossil discoveries of Australopithecus afarensis. Research into other hominins, like the “First Family” fossils discovered near Lucy’s site, suggests that these early humans formed social groups of about 15 to 20 individuals. These groups likely worked together to forage for food, protect each other from predators, and care for one another.

Lucy’s species also exhibited some intriguing social behaviors. Evidence from other fossils of A. afarensis suggests that they cared for each other, even in the face of injury. A healed bone fracture found in another A. afarensis individual supports the idea that these hominins provided social support to injured members, much like modern primates.

Lucy’s Legacy: How She Changed the Study of Human Origins

The discovery of Lucy completely transformed the field of paleoanthropology. Before her, the prevailing theory held that human ancestors evolved from apes in a linear progression, with larger brain size being the defining feature of evolution. However, Lucy’s combination of apelike features (such as a small brain and long arms) with humanlike traits (such as bipedalism) challenged this simplistic view of human evolution.

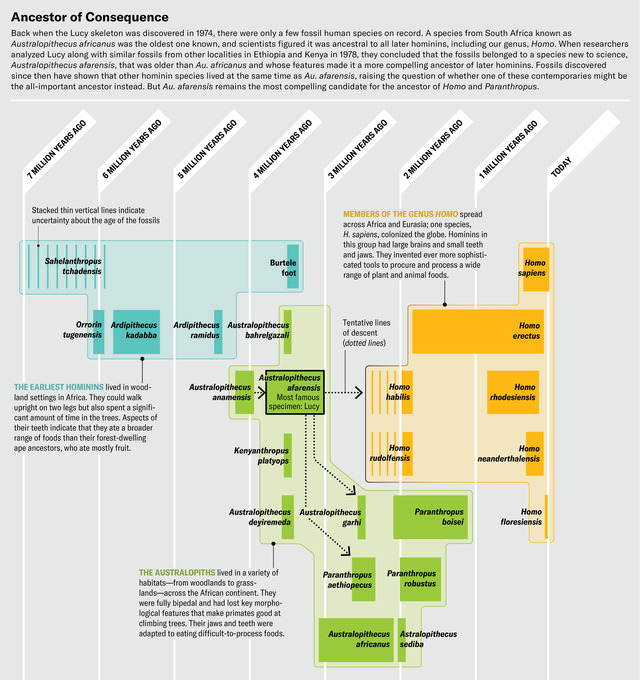

The fossil prompted scientists to reconsider the significance of Australopithecus afarensis in the human lineage. Lucy and her species provided compelling evidence that bipedalism, rather than increased brain size, was a key adaptation that distinguished early humans from other primates. This led to the recognition of A. afarensis as a crucial species in the evolutionary tree, one that could have given rise to later hominin species, including Homo.

New Discoveries and Ongoing Research on A. afarensis

The legacy of Lucy’s discovery continues to impact the field. New fossils of A. afarensis have been uncovered, providing even more insights into the life and behaviors of this early human ancestor. Sites like Hadar and Laetoli in Tanzania have yielded additional remains that help flesh out our understanding of how A. afarensis lived, interacted, and evolved.

Ongoing excavations in Ethiopia’s Afar Rift and other parts of East Africa continue to reveal more about Lucy’s species. These new fossils contribute to a more detailed picture of A. afarensis and its place in the broader story of human evolution.

Contemporary Hominins: Was Lucy the Only One?

While Lucy’s species was long considered the only hominin present during her time, recent discoveries have shown that A. afarensis lived alongside other hominin species. Fossils found at sites such as Woranso-Mille in Ethiopia suggest that multiple species coexisted in East Africa between 3.5 and 3.0 million years ago. This raises the question of whether Lucy’s species was the direct ancestor of Homo or whether another species might have played a more prominent role in the evolution of humans.

The discovery of A. deyiremeda, another hominin species coexisting with A. afarensis, further complicates the evolutionary picture. While A. afarensis remains the most likely ancestor of Homo, these new findings highlight the diversity of early hominins and the complexity of the human family tree.

Lucy’s Place in the Hominin Family Tree

Lucy’s importance in the human evolutionary timeline cannot be overstated. While new discoveries continue to challenge our understanding of human evolution, A. afarensis remains a key species in the story of our origins. The anatomical and behavioral traits of Lucy and her kind provide crucial insights into the evolutionary steps that led to the emergence of Homo sapiens.

As anthropologists continue to explore the fossil record, the role of A. afarensis and Lucy’s place in the human lineage will remain a subject of intense research. Her discovery marked the beginning of a new era in understanding our ancient ancestors, and her legacy will continue to shape the field of paleoanthropology for years to come.

Video

Watch the video Life and Death 3,000,000 Years Ago: Lucy.

Conclusion: Lucy’s Continuing Influence on the Evolutionary Narrative

The discovery of Lucy remains one of the most significant breakthroughs in the study of human origins. Her fossil provides an unparalleled glimpse into the past, offering scientists a clearer understanding of how early hominins lived, adapted, and evolved. While much remains to be uncovered, Lucy’s legacy is undeniable. As research continues and new discoveries are made, Lucy will remain a touchstone in the ongoing quest to understand the origins of humanity.