In the tense years of the Cold War, the U.S. military’s race to maintain a constant nuclear deterrent came with terrifying risks. In 1961, a disastrous accident nearly turned an ordinary air mission into a global catastrophe. As a B-52 bomber broke apart mid-flight over North Carolina, it dropped two powerful nuclear bombs, each capable of mass destruction. Miraculously, a series of lucky circumstances prevented the unthinkable. The events of that fateful day, however, serve as a chilling reminder of the dangers posed by the pursuit of nuclear supremacy.

The Goldsboro Incident: A Narrow Escape from Disaster

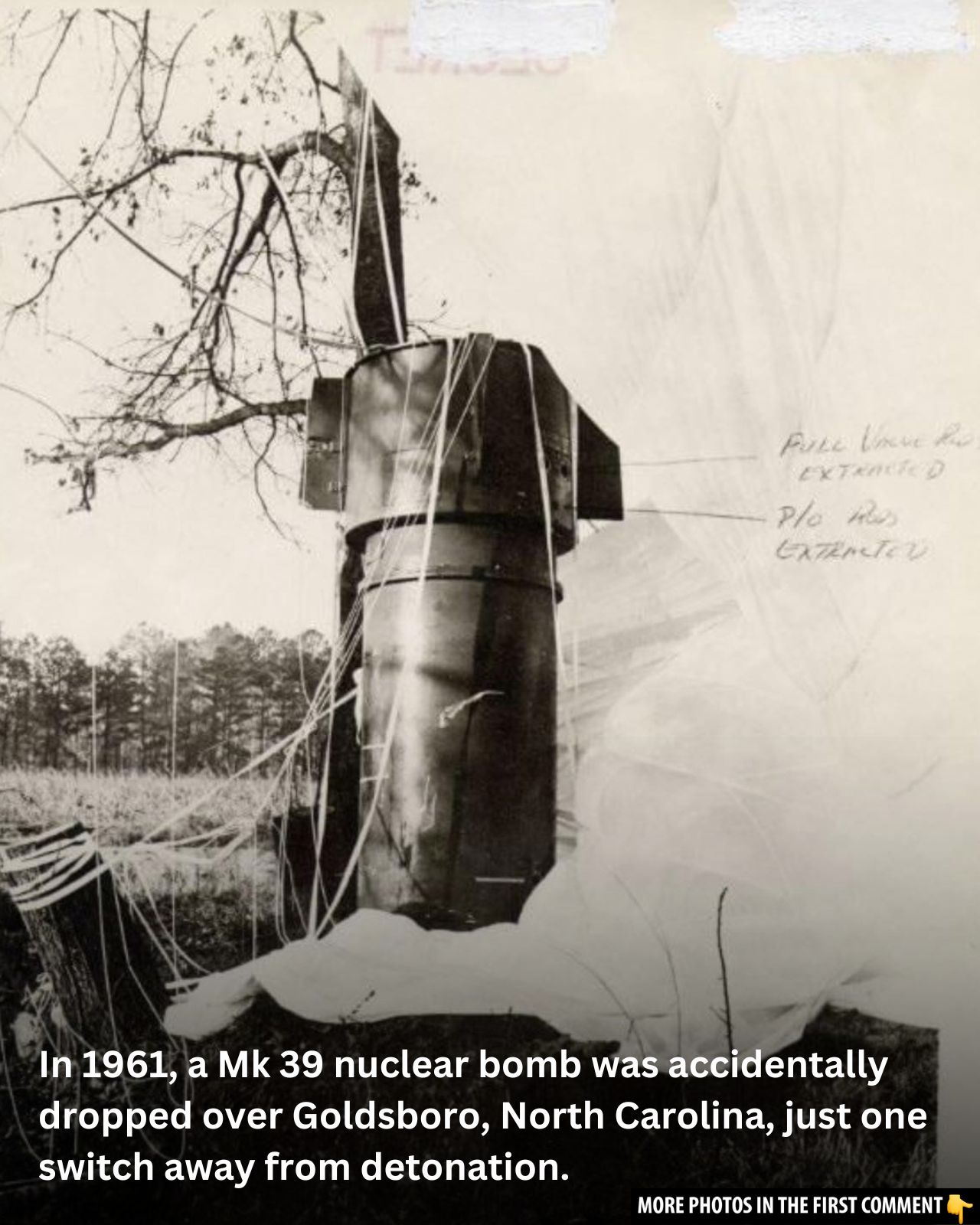

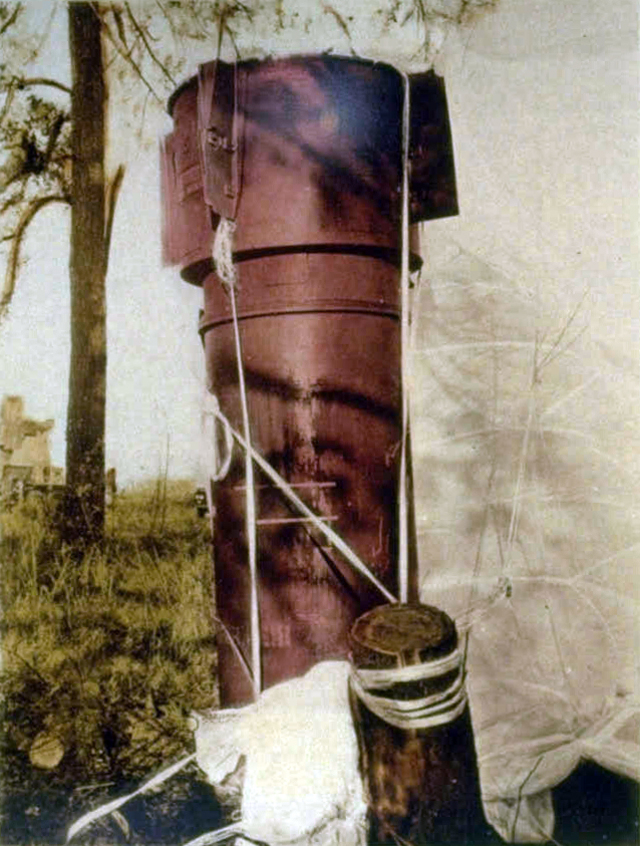

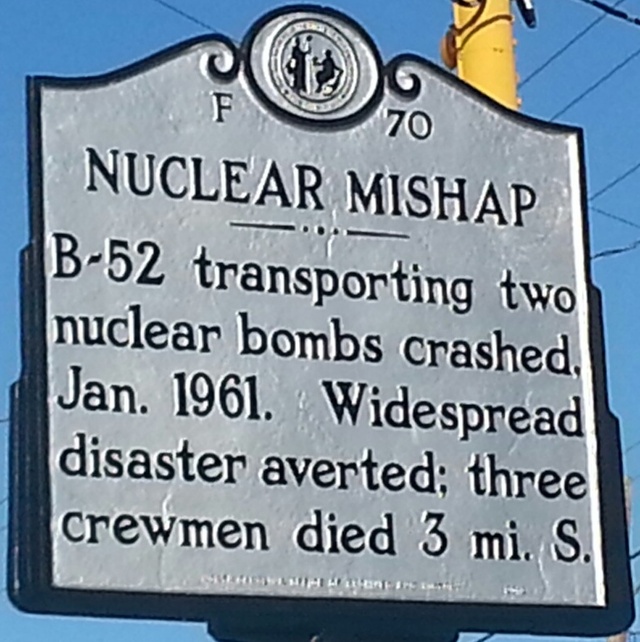

On the night of January 23, 1961, a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress was returning to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina after a refueling operation. As it neared the base, the plane suffered a catastrophic structural failure and disintegrated mid-air. In the process, it dropped two 3.8-megaton Mark 39 nuclear bombs over a rural farming community. Miraculously, the crew ejected safely, and the bombs plunged to the ground.

One bomb landed in a tobacco field, while the other descended slowly, thanks to a parachute, and landed near a tree. This bomb came terrifyingly close to detonating. According to a declassified government document, three of its four safety mechanisms failed, and it was only by “dumb luck” that the bomb didn’t explode. If it had detonated, the explosion would have been 260 times more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima, potentially wiping out an entire region, with radioactive fallout extending as far as New York City.

Video

Watch the video How the US Accidentally Dropped Nukes on Itself and Its Allies to uncover the shocking true stories of nuclear mishaps.

1958: A Year of Nuclear Mishaps

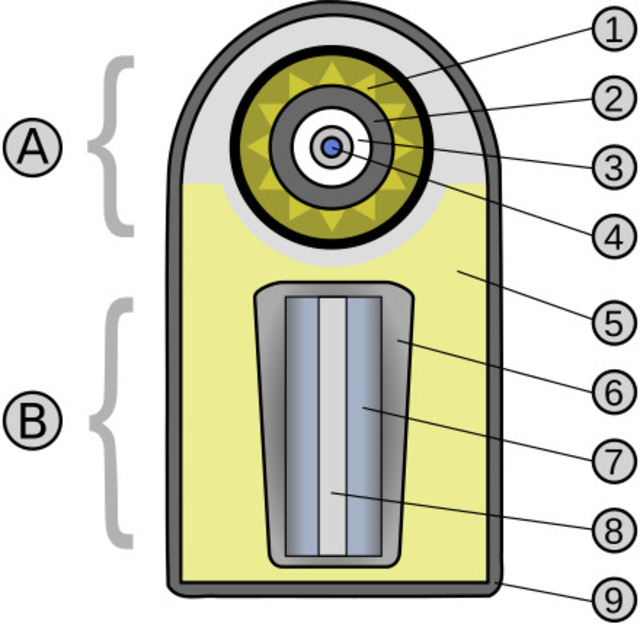

The Goldsboro incident was not an isolated case. The year 1958 alone saw a shocking eight nuclear weapons accidents. One of the most infamous occurred near Florence, South Carolina, where a Mark 6 bomb fell from a B-47 bomber. The bomb’s high explosives detonated on impact, creating a 35-foot-deep crater, injuring six people, and destroying a nearby house. The bomb’s nuclear core had been stored separately, so the potential for a nuclear explosion was avoided, but the incident left an indelible mark on both the local community and the military.

Even though these accidents were downplayed and largely forgotten in the public sphere, they underscored the inherent risks of maintaining nuclear weapons in a state of constant readiness. The “broken arrow” term was coined to describe these accidents, where a nuclear weapon was lost, mishandled, or detonated accidentally. The Department of Defense officially acknowledged only 32 broken arrows, but historians and analysts like Stephen Schwartz argue that the number of close calls was far greater.

Human Error and “Broken Arrow” Accidents

The causes of these accidents were often not the result of technological failure, but human error. In the South Carolina incident, for example, a crew member inadvertently hit a release switch, causing the bomb to fall from the aircraft. As the bomb plummeted to the ground, the crew member barely managed to escape by grabbing a handhold at the last moment. In another instance, a fire started on the aircraft after seat cushions were placed on a hot-air vent, forcing the crew to abandon the plane.

These incidents highlight the fallibility of human beings. As Schwartz points out, the design and maintenance of nuclear weapons systems involve human hands at every stage. While engineering advancements allowed for safety measures, human error still played a pivotal role in these close calls. The military’s obsession with maintaining readiness—combined with the sheer number of nuclear weapons being produced—meant that accidents were almost inevitable.

The Role of Technological Safety Features

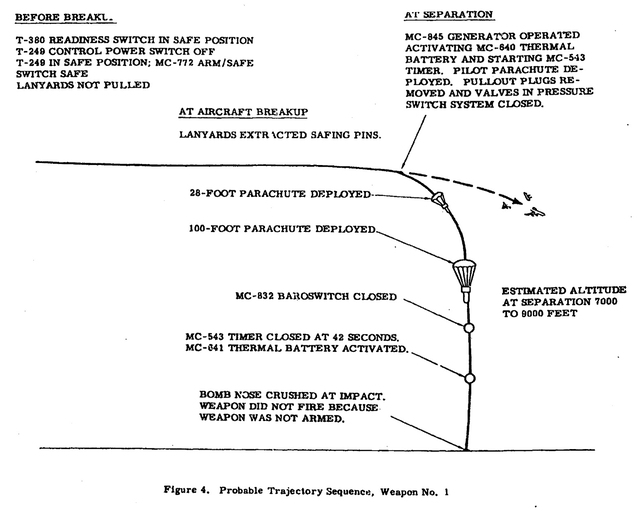

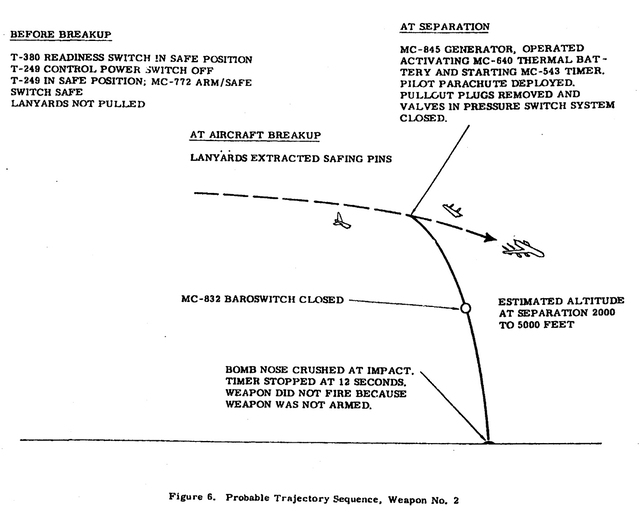

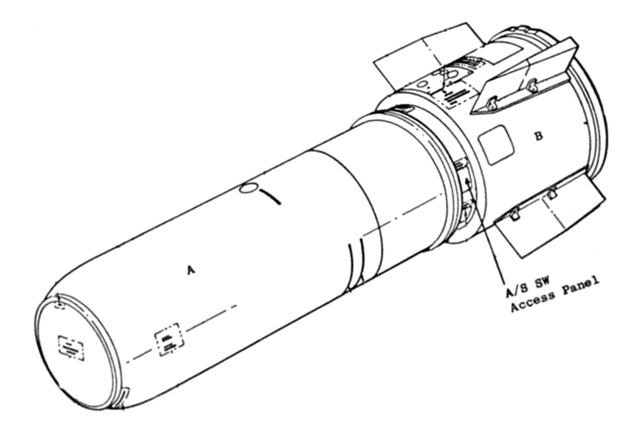

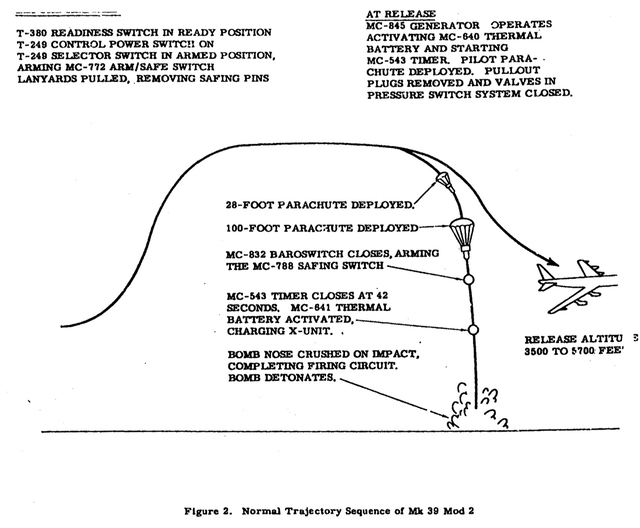

The critical factor that saved the world from a nuclear catastrophe was the safety mechanisms built into these weapons. The Mark 39 bombs involved in the Goldsboro incident were equipped with multiple layers of protection, including the MC-772 Arm/Safe switch, which ensured that the bomb could not be detonated unless specific conditions were met.

In the case of Bomb No. 1, the parachute-equipped weapon, the safety mechanisms worked as intended, and the bomb did not explode. However, for Bomb No. 2, the free-falling bomb, the safety systems failed to engage fully. The parachute did not deploy, and the timer failed to complete its countdown. Still, this bomb, too, failed to detonate due to a fault in the arming system. Despite the initial shock of its impact and the widespread destruction it caused, the bomb did not explode. Technological safeguards and pure luck spared the U.S. and its allies from a disastrous nuclear explosion.

The Global Implications of U.S. Nuclear Accidents

The U.S. Air Force’s nuclear accidents did not only affect the United States. The implications of such mishaps reached beyond American borders, causing concerns among U.S. allies. The 1966 accident near the Spanish coast, where a B-52 bomber dropped a nuclear bomb into the sea, and the 1968 accident in Greenland, which spread radioactive materials over the Arctic ice, both highlighted the potential risks of storing and transporting nuclear weapons across the globe. These accidents were stark reminders of the dangers posed by the Cold War’s nuclear arms race.

The accidents also strained the relationships between the U.S. and its NATO allies, who were often involved in the storage and transportation of nuclear weapons across Europe. The damage to U.S. credibility and the fears of a nuclear detonation were significant enough to lead to the eventual cessation of the airborne alert program in 1968.

The End of the Airborne Alert Program

In the wake of these near-disasters, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara finally put an end to the airborne alert program in 1968. The decision was influenced by the growing concerns over the frequency of these accidents, as well as the increased reliance on more stable missile-based nuclear deterrence strategies. The air force’s continual readiness to deploy nuclear bombs at a moment’s notice had led to an era of dangerous negligence, and McNamara recognized that the risks far outweighed the potential rewards.

The end of the airborne alert program marked a significant shift in U.S. military policy and the way nuclear weapons were handled. With the rise of missile-based nuclear deterrence systems, the risk of accidents involving bombers decreased significantly. However, the legacy of the “broken arrow” incidents would remain a dark chapter in the Cold War history.

Legacy of the Goldsboro Accident and Nuclear Weapon Safety

The Goldsboro accident had a profound impact on the design and safety protocols for nuclear weapons. Following the event, the U.S. government made several safety modifications to its nuclear weapons arsenal. In particular, the MC-722 Arm/Safe switch was replaced with a more advanced version to ensure that a “broken arrow” incident could never happen again.

Additionally, the accident led to greater transparency and oversight in the handling of nuclear weapons. In the years that followed, nuclear weapon safety became a priority, and many of the lessons learned from the Goldsboro incident informed future policies and protocols regarding the storage and transportation of nuclear arms.

Video

Watch the video Hiroshima: Dropping the Bomb to explore the events leading up to one of history’s most devastating moments.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned from Close Calls

The 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash and the subsequent nuclear weapons accidents serve as a stark reminder of the dangers inherent in the Cold War’s nuclear arms race. While no nuclear bombs detonated during these mishaps, the close calls highlighted the fragile nature of global security during this tumultuous period in history. The careful engineering of safety mechanisms and sheer luck played pivotal roles in preventing a nuclear catastrophe, but the events serve as a testament to the need for vigilance and responsibility in handling such powerful weapons.

The end of the airborne alert program and the subsequent safety improvements were steps in the right direction, but the history of these accidents reminds us of the fragility of the world’s peace and the importance of maintaining rigorous safety standards in the handling of nuclear arms. In the end, we are lucky that these incidents did not lead to disaster—this time, dumb luck and engineering genius were enough to avert the unimaginable.