The history of money is a complex and debated topic that has fascinated scholars for centuries. While the origins of currency have often been attributed to either commodity-based or state-controlled models, a recent theory put forward by archaeologist Dr. Mikael Fauvelle is challenging conventional views. In his groundbreaking study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, Fauvelle argues that money didn’t arise from within communities or through state enforcement, but instead emerged primarily as a tool to facilitate long-distance trade between strangers. This new approach, which Fauvelle calls the “trade theory of money,” opens up a fresh perspective on the birth of money and its pivotal role in human history.

The Traditional Theories of Money: Commodity and Chartalist Models

The origins of money have been widely debated for centuries, and two traditional theories dominate this discussion: the “money as commodity” theory and the “chartalist” theory.

The money as commodity theory suggests that money emerged from the limitations of barter. In barter systems, both parties need something the other desires, which often leads to inefficiencies. Thinkers like Aristotle and economist Carl Menger proposed that commodities like metals (gold, silver) became money because they were durable, valuable, and easy to carry. This theory holds that money emerged naturally as a solution to the inefficiencies of barter.

On the other hand, the chartalist theory argues that money was created by states to serve as a unit of account for taxation and government spending. According to this view, money was a state-imposed tool to regulate the economy and standardize payments. While this theory explains the role of money in state economies, it doesn’t fully account for the emergence of money in pre-state societies.

Both of these theories have contributed to our understanding of the origins of money, but they fail to explain how currency emerged in regions without centralized state control or formal taxation systems. This gap in the traditional models is where Fauvelle’s “trade theory of money” offers a new, complementary perspective.

Video

Check out the video on a new study suggesting money originated to facilitate long-distance trade between strangers – it’s an intriguing theory!

Dr. Fauvelle’s “Trade Theory of Money”: A New Approach

Dr. Mikael Fauvelle’s “trade theory of money” provides a fresh perspective on the origins of currency. Instead of solely attributing the development of money to bartering or state control, Fauvelle suggests that money emerged as a practical solution to facilitate long-distance trade between unfamiliar groups. In pre-state societies, people engaged in trade across vast distances, often encountering strangers with different languages and customs. Trust-based systems like barter were not sufficient in these scenarios, which increased the demand for a widely accepted, portable medium of exchange.

Fauvelle argues that money emerged to overcome the challenges posed by long-distance trade. This theory highlights the importance of money as a tool for intercultural exchange, making transactions more efficient and enabling people to trade goods even when they didn’t share a common language or customs. By focusing on the practical needs of traders, Fauvelle’s theory introduces the idea that money was not just an economic tool but a way to bridge gaps between distant, often disconnected, communities. This approach opens up new avenues for studying the evolution of money, especially in regions and periods not yet fully explored.

The Role of Money in Intercultural Exchange

What makes Fauvelle’s theory particularly compelling is the way it explains the role of money in intercultural exchange. Before the advent of money, trade was often limited to exchanges within familiar communities, where people shared common languages, customs, and economic practices. But as trade expanded to distant and unfamiliar groups, the need for a universally accepted and easily transferable form of currency became crucial. Money, in this sense, allowed people to bypass the complexities of bartering, enabling them to transact efficiently even with strangers who might have different customs and expectations.

Fauvelle’s theory also challenges the notion that money was simply a tool for elites or governments to control economic systems. Instead, he argues that money emerged as a practical innovation for everyday people who were involved in long-distance trade. This view not only provides a new perspective on the origins of money but also emphasizes its role as a tool for social connection, making it easier for diverse and distant groups to engage in mutually beneficial exchanges.

Money Beyond a Commodity: Social and Cultural Dimensions

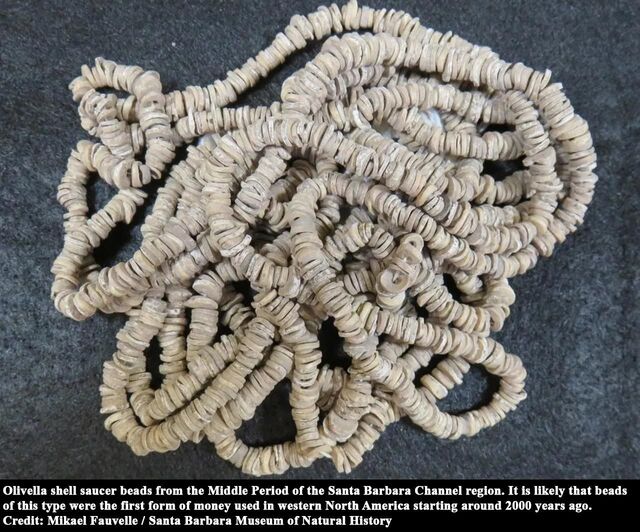

While the primary role of money was undoubtedly as a medium of exchange, Fauvelle’s theory also highlights its social and cultural significance. In both pre-Columbian North America and Bronze Age Europe, the use of shell beads and bronze ingots went beyond mere economic transactions. In some cases, these materials also held symbolic and ritual significance. Shell beads, for example, were not only used in trade but also in ceremonial contexts, indicating that money had broader social meanings. Similarly, in Bronze Age Europe, the widespread use of bronze ingots may have contributed to the development of social hierarchies, as the control over these valuable resources could concentrate wealth and power in the hands of elites.

The social dimensions of early currency suggest that money was not only a tool for economic efficiency but also a symbol of status and cultural identity. This underscores the complex ways in which money influenced not just trade, but also the formation of social structures and cultural practices in ancient societies.

The Global Spread of Money: Examining Other Regions

While Fauvelle’s research focuses on North America and Europe, he suggests that similar processes may have occurred in other parts of the world. Ancient Mesoamerica and the Pacific Islands are two regions where the need for long-distance trade might have led to the emergence of currency. In these areas, complex trade networks existed long before the rise of centralized states, and the need for a universally accepted medium of exchange could have driven the development of money.

The global spread of trade and the associated need for currency likely led to the independent emergence of money in various regions, each shaped by local customs, resources, and needs. Fauvelle’s theory opens the door for further research into the origins of money, encouraging scholars to explore how different societies developed their own forms of currency to facilitate trade.

Video

Watch the video to explore the new theory that money originated from long-distance trade – it’s an interesting perspective!

Conclusion: A Revolutionary Perspective on the Origins of Money

Dr. Mikael Fauvelle’s “trade theory of money” offers a revolutionary new perspective on the origins of currency, challenging traditional theories that focus on barter or state control. By emphasizing the role of long-distance trade in the emergence of money, Fauvelle’s theory provides a more nuanced understanding of how and why money developed as a tool for human exchange. His research underscores the importance of money not just as an economic tool but also as a social and cultural force that connected distant groups, facilitated trade, and shaped the course of history.

As the study of ancient currencies continues to evolve, Fauvelle’s work promises to be a catalyst for further research into the complex history of money, offering new insights into the role of trade, social exchange, and human innovation in the development of economic systems. This research not only enriches our understanding of the past but also offers valuable lessons for the future of global trade and economics.