Buried beneath the fields of Norfolk, a hidden treasure lay undisturbed for over 2,000 years—until a plow struck gold. The Snettisham Hoards, the largest collection of Iron Age metalwork in Europe, have puzzled archaeologists for decades. Were these torcs and ornaments offerings to the gods, hidden wealth, or symbols of power? With each discovery, new clues emerge, reshaping our understanding of Iron Age Britain. What secrets does this golden legacy still hold?

The Snettisham Hoards: A History of Discovery

Video

The First Discovery: A Chance Encounter (1948)

In November 1948, Raymond Williamson, a tractor driver working near Ken Hill, Norfolk, struck something solid with his plow. Dismissing it as scrap metal, he discarded it—until experts later identified the pieces as gold torcs from the Late Iron Age.

The ‘Great Torc’ and Royal Interest (1950)

Two years later, another plowman, Tom Rout, uncovered the now-famous “Great Torc.” This finely crafted neck ring, featuring intricate Celtic art, gained national attention. According to legend, it was even shown to King George VI at nearby Sandringham Estate.

Renewed Excavations and the Expanding Treasure Trove (1990–Present)

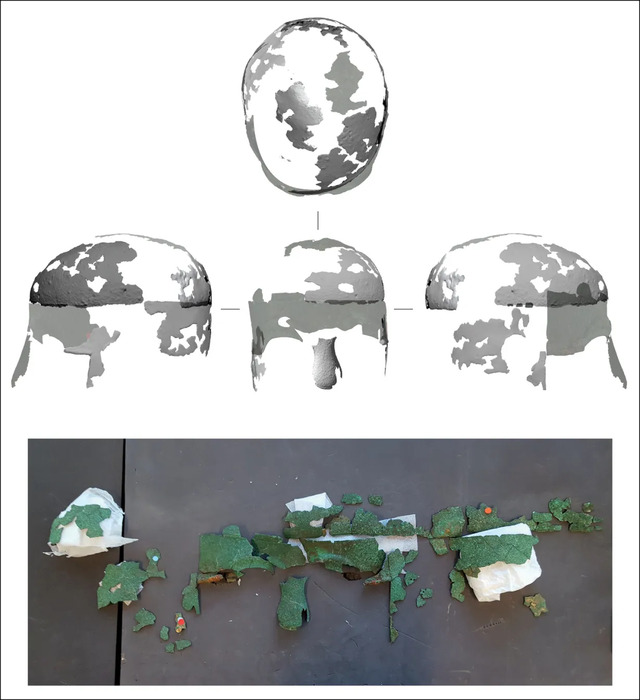

For decades, archaeologists believed the site had been fully explored—until Cecil ‘Charles’ Hodder, a metal detectorist, discovered over 500 fragments of metalwork buried inside an upturned bronze helmet in 1990. This led to large-scale excavations, revealing more than 1,200 artifacts between 1990 and 1992.

Subsequent fieldwork in the 2000s and 2010s has further expanded the hoards, with many pieces now housed in the British Museum and Norwich Castle Museum.

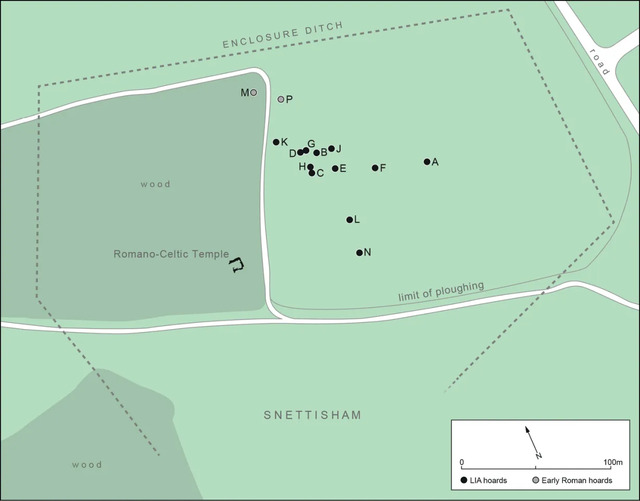

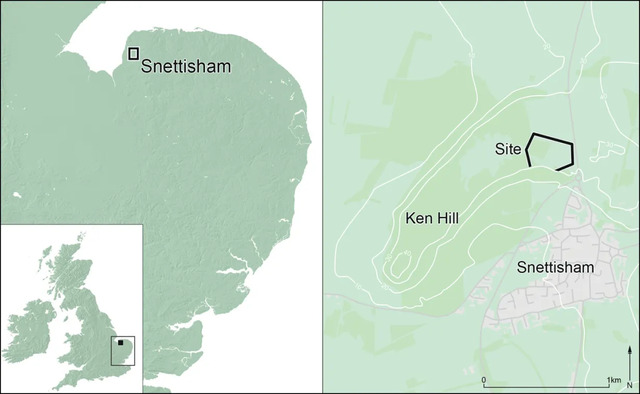

The Landscape of Snettisham

Ken Hill, overlooking the Wash, was a prominent location in the Iron Age. Over 2,500 years ago, rising sea levels made it a natural peninsula, surrounded by water on three sides. This geographical isolation may have given it a ritual significance, making it an ideal site for ceremonial burials or offerings.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Snettisham was an important site long before the hoards were buried. The area shows signs of feasting, gatherings, and enclosures, indicating it was a place of communal activity and ritual importance.

By the early Roman period (1st–4th century AD), the site had been partially enclosed with V-shaped ditches, possibly as a temple complex or a place of tribute.

Understanding the Hoards: What Was Buried?

The hoards contain an unprecedented number of metal objects, including:

- 60+ complete or nearly complete torcs (more than anywhere else in Europe).

- Gold, silver, and bronze bracelets, rings, and ingots.

- A bronze helmet used as a container for fragmented torcs.

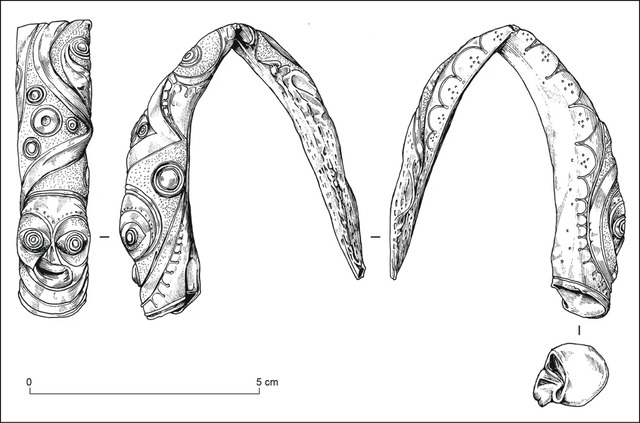

Torcs were prestigious items, worn by warriors, leaders, and possibly religious figures. Each piece was unique, suggesting they were personalized symbols of status rather than mass-produced jewelry.

One of the most intriguing finds was a bronze helmet filled with gold fragments. This is the only known example of such a practice in Iron Age Britain, raising questions about its significance—was it a war trophy, a ritual deposit, or a hidden treasury?

Iron Age Craftsmanship: Technology and Innovation

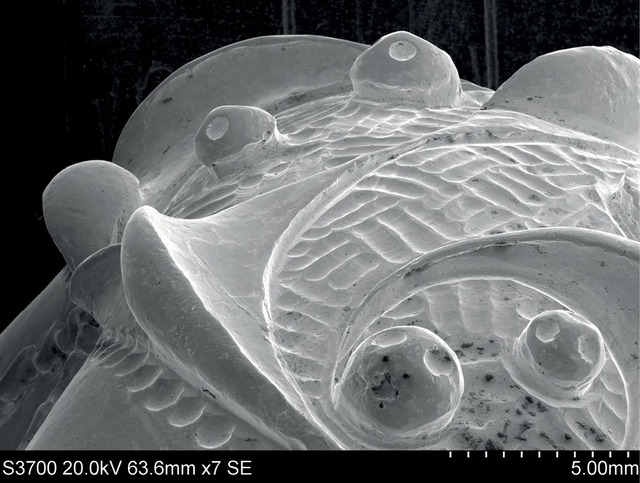

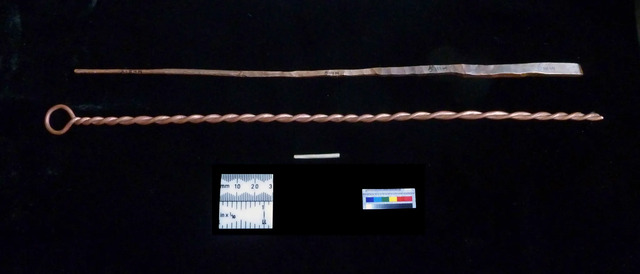

Scientific analysis has revealed the sophisticated metalworking techniques used to create the torcs, including:

- Twisting and coiling gold wires to form decorative patterns.

- Surface enrichment, a technique that increased the gold content on the outer layer.

- Gilding with mercury, the earliest known example of this method in Britain.

Some torcs contained wooden cores to maintain their shape. Scientists identified the wood types as hazel, elder, and dogwood, showing the careful material selection of Iron Age metalworkers.

The Mystery of the Burials: Why Were They Hidden?

Archaeologists suggest two primary theories for why these treasures were buried:

- Ritual Deposits – The torcs may have been offerings to deities, placed in the ground at a sacred site.

- Hidden Wealth – They could have been a treasury or emergency hoard, concealed during times of war or social instability.

Around 60 BC, as torcs were being buried, gold coins began circulating in East Anglia. Some scholars suggest this marks a cultural transition—as coinage became the dominant form of wealth, traditional symbols like torcs lost their importance.

Was Warfare a Factor? The 1st century BC was a turbulent period in Britain. Could these hoards be linked to:

- Tribal conflicts between local Iron Age groups?

- The increasing influence of Roman trade and politics?

The exact reason remains unknown, but the timing suggests a period of significant social change.

The Future of Snettisham: Conservation and Research

Despite decades of excavation, many questions remain. Researchers are using modern technology to uncover new insights, including:

- 3D scanning to digitally reconstruct how torcs were worn.

- Geophysical surveys to locate undiscovered hoards.

- Chemical analysis to trace the origins of the gold and silver.

The British Museum and Norwich Castle Museum continue to study and display these artifacts, ensuring that the legacy of Snettisham is preserved for future generations.

Could There Be More Hoards? Given that new finds continue to emerge, it’s possible that more treasures still lie buried beneath the fields of Norfolk.

Conclusion

The Snettisham Hoards remain one of the most significant Iron Age discoveries in Europe, offering a rare glimpse into the wealth, artistry, and beliefs of ancient Britain.

From the craftsmanship of the torcs to the mystery of their burial, Snettisham provides crucial evidence of how Iron Age society functioned and evolved.

Although the full story of the hoards may never be known, one thing is certain: Snettisham’s golden legacy continues to shine, revealing more about Britain’s past with each new discovery.

As research advances, who knows what secrets still lie buried beneath the fields of Norfolk?

Video

Check out the video to see archaeologists uncover an extraordinary hoard in an Anglo-Saxon cemetery, featured in Time Team | Chronicle. This discovery is truly remarkable!