For centuries, the Kingdom of Kush, a powerful African civilization that flourished long before much of the modern world had taken shape, was nearly forgotten by history. Yet, in the arid landscapes of Sudan, a treasure trove of ancient pyramids, temples, and artifacts offers a window into the incredible achievements of the Kushites. One of the most fascinating chapters of African history, the Kingdom of Kush not only rivaled Egypt in influence but also left behind a lasting cultural and architectural legacy that still resonates today. This journey through the ancient land of Kush uncovers its rise, cultural grandeur, fall, and rediscovery, offering a glimpse into an empire that shaped the course of history but has long been overshadowed.

The Rise of Meroe: Kush’s Royal Capital

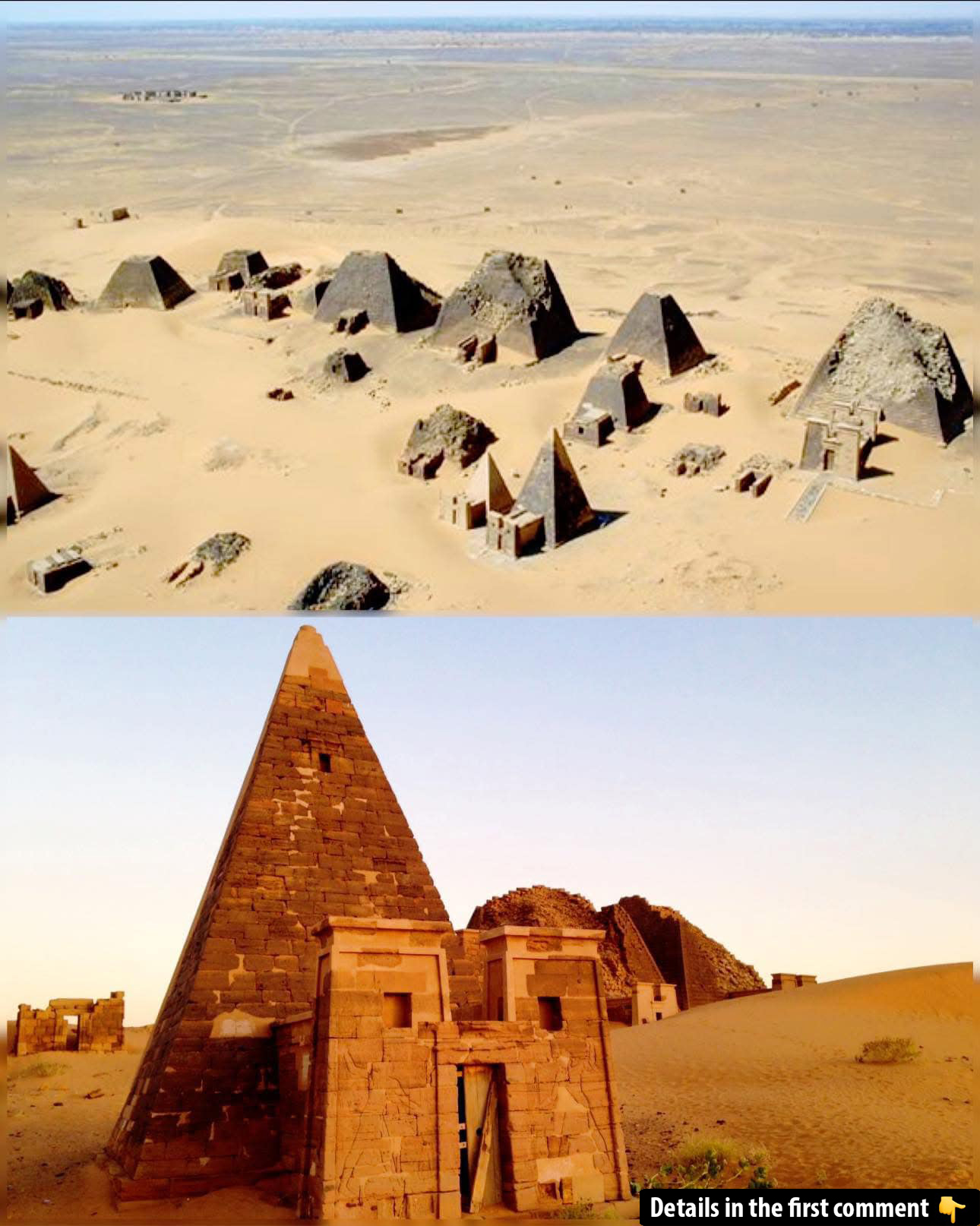

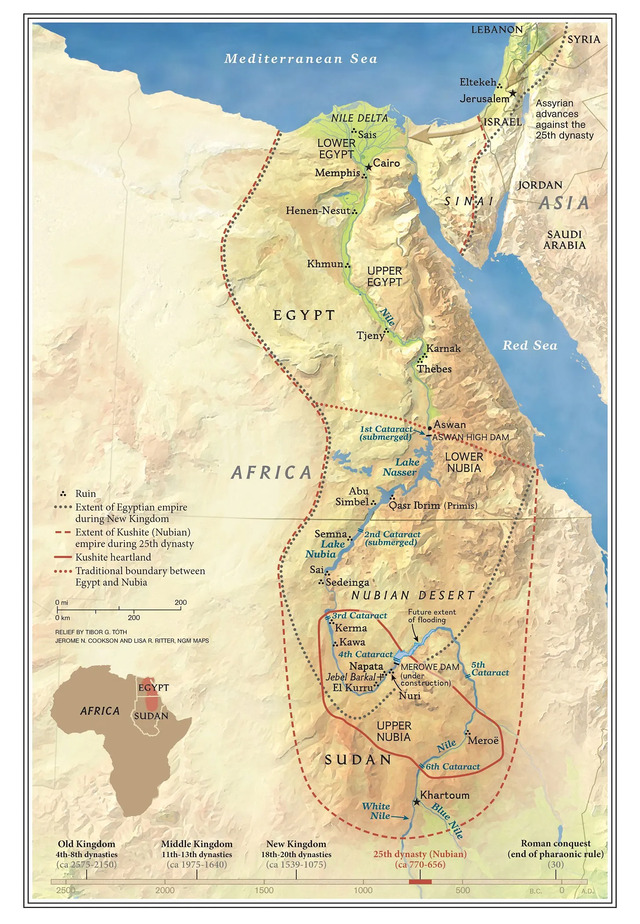

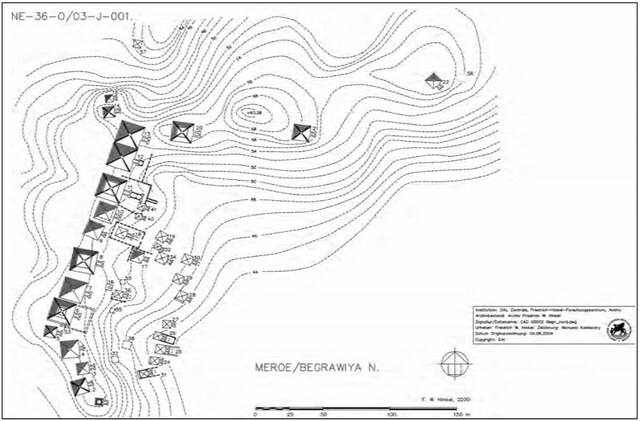

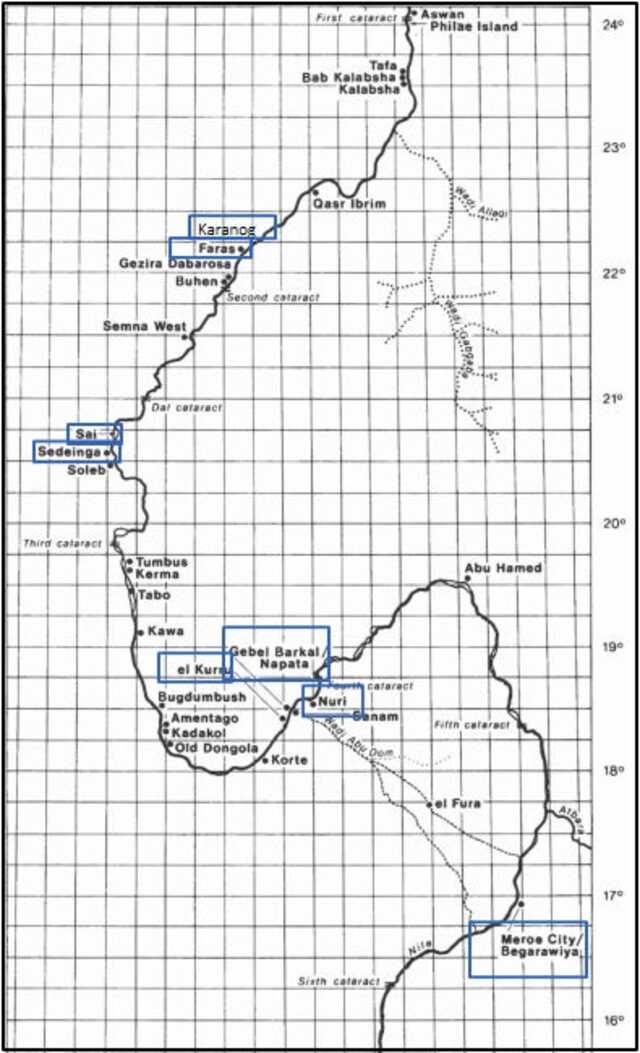

Nestled 150 miles north of Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, lies Meroe—once the heart of the Kingdom of Kush. This ancient city became the epicenter of Kushite power and culture, famous for its impressive pyramids, royal palaces, and temples. Meroe served as the royal capital for centuries, its pyramid fields rivaling Egypt’s Giza in both grandeur and cultural significance.

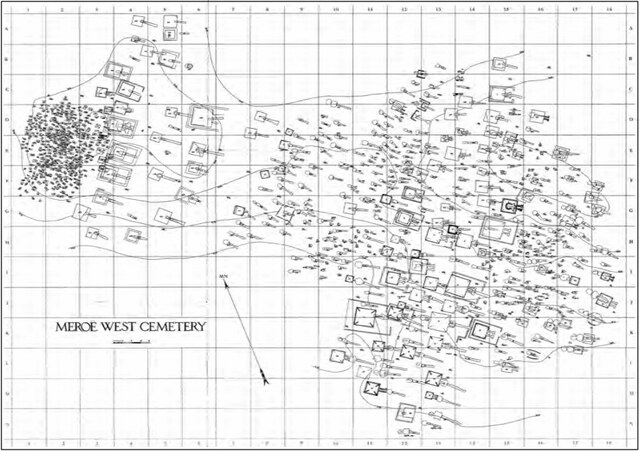

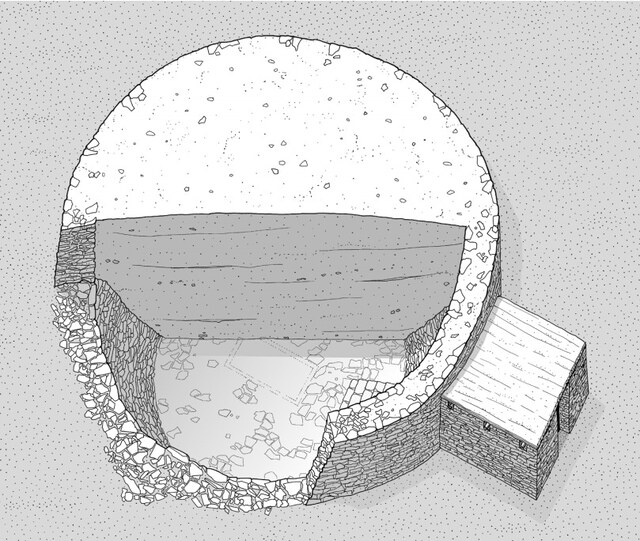

But Meroe was more than just a burial ground; it was a thriving city that epitomized Kush’s wealth, power, and influence over a vast region of Africa. A glimpse of Meroe’s royal cemetery, with over 50 pyramids, each distinct in height and construction, reveals not just the art of monumental architecture, but the spiritual beliefs that bound the people of Kush to their kings, queens, and gods.

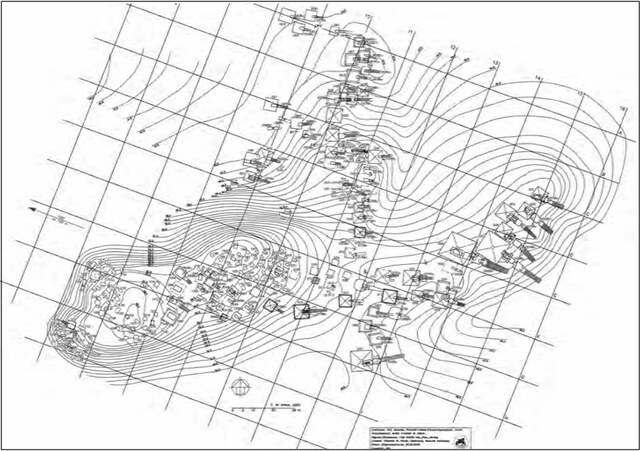

The royal city of Meroe, to the west of the cemetery, houses the remains of a palace, a temple, and a royal bath—testaments to the luxury and sophistication of Kushite civilization. These ruins, adorned with a blend of Egyptian, Greco-Roman, and local influences, show that Meroe was not isolated but deeply connected to the wider Mediterranean and African worlds.

Video

Watch the video “Kingdom of Kush – History of Africa with Zeinab Badawi” to learn about this ancient civilization.

The Legacy of the Pyramids: Monuments of Kushite Power

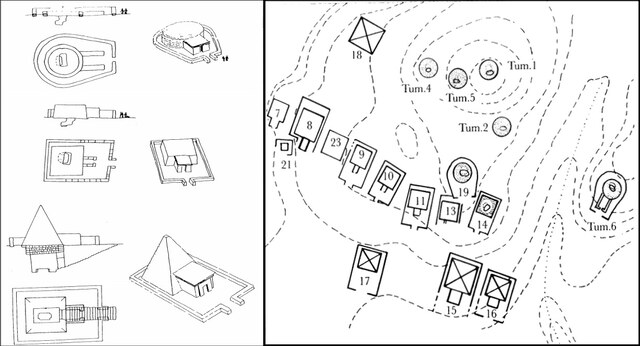

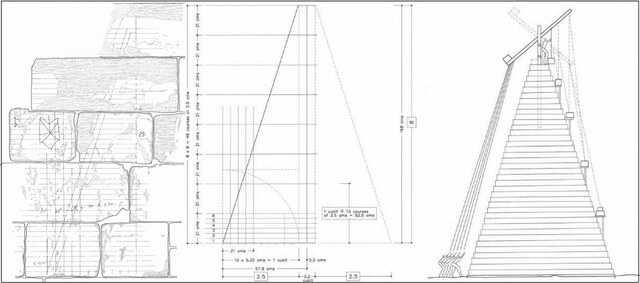

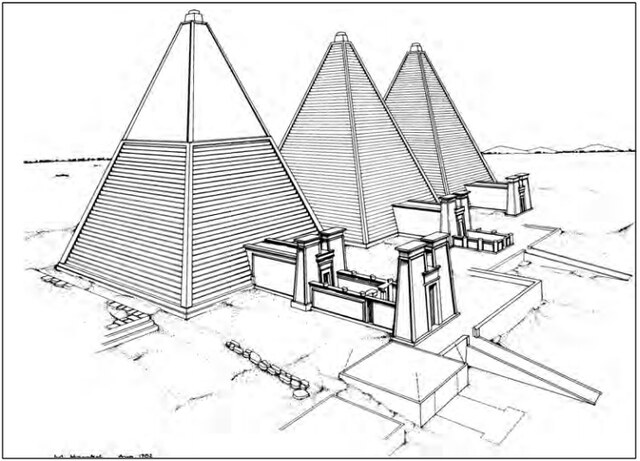

The most enduring symbols of the Kingdom of Kush are the pyramids of Meroe, which stand as a testament to the civilization’s architectural prowess. Unlike Egypt’s grand pyramids, the Meroe pyramids are steeper and smaller, but they boast a unique design and construction style that set them apart.

More than 200 pyramids have been discovered in Sudan, surpassing the number found in Egypt. These pyramids were not reserved solely for royalty; elites, including nobles, were also buried in these sacred structures, illustrating the democratic nature of Kushite society when it came to commemorating the deceased.

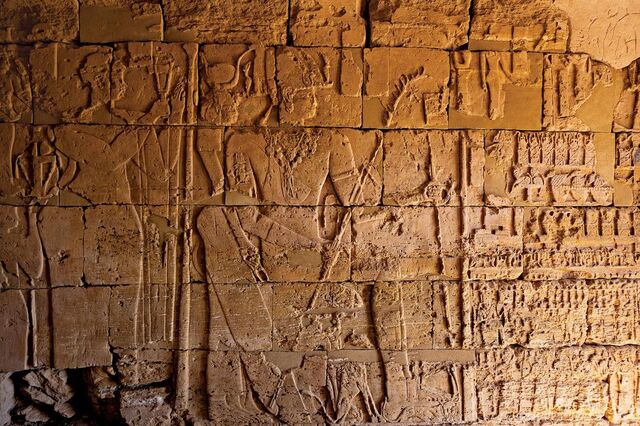

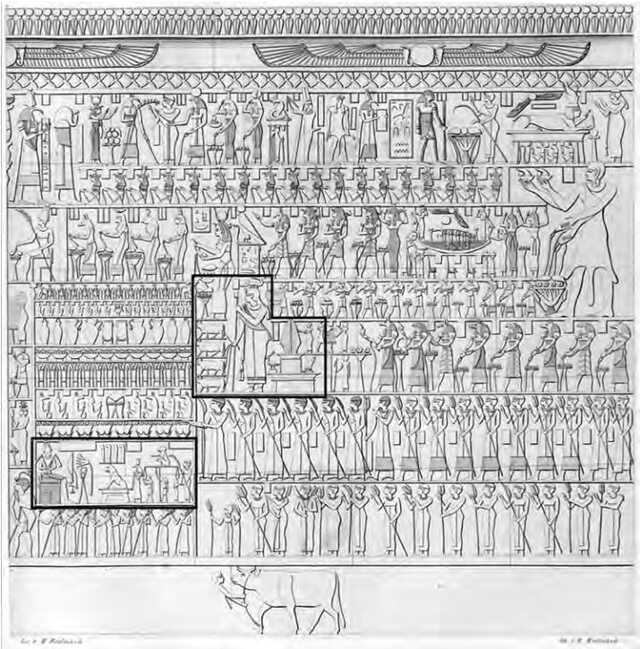

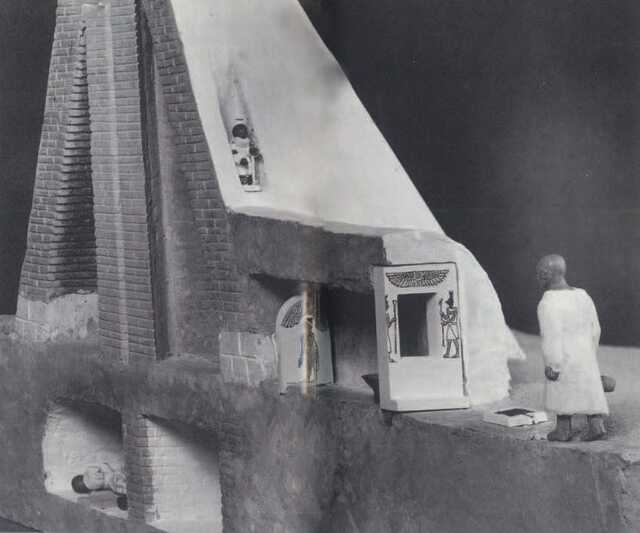

The pyramids of Meroe were more than just tombs; they were symbols of Kushite power, religious beliefs, and societal organization. At the peak of the kingdom, each pyramid was built as part of a larger mortuary complex, complete with temples, offering chapels, and statues of the deceased. The elaborate artwork found inside these structures, particularly in the royal tombs, shows scenes of the deceased’s journey to the afterlife, reinforcing the Kushite belief in resurrection and the eternal power of the royal family.

Kush and Egypt: A Shared History of Kings and Conquerors

Kush’s relationship with Egypt was both complex and symbiotic. Throughout much of its history, the Kingdom of Kush and Egypt coexisted, at times as rivals, at other times as allies. By the 8th century BCE, the Kingdom of Kush had grown powerful enough to assert itself as Egypt’s equal. Under the reign of Piye, the Kushites conquered Egypt and established the 25th Dynasty, also known as the “Black Pharaohs.” This marked the first time that African rulers, rather than Egyptians, sat on the throne of Egypt.

The Black Pharaohs not only ruled Egypt but also revived many aspects of Egyptian religion, culture, and architecture. They championed the building of pyramids and temples, reasserting the ancient Egyptian traditions of burial and worship. Piye’s conquest of Egypt was commemorated in a monumental inscription, recorded on a granite stela, that detailed his military victories and the reinstitution of the pharaonic traditions in Egypt.

Kandakes: The Powerful Queens of Kush

While the men of Kush were often hailed as conquerors, it was the queens, known as Kandakes (or Candaces), who played an equally vital role in the kingdom’s political and military power. These powerful queens, including the famous Amanirenas, led armies into battle, protecting Kush from Roman invaders and asserting their kingdom’s independence. Amanirenas, described as a “masculine sort of woman” by the Greek geographer Strabo, famously fought off Roman forces, returning to Meroe with the bronze head of Emperor Augustus, which she buried beneath a temple dedicated to victory.

The importance of the Kandakes is not only evident in their military prowess but also in their religious and cultural influence. The Meroitic kingdom, under the rule of these queens, became a beacon of political stability, spiritual significance, and economic power. Queens like Amanirenas and Amanitore were instrumental in preserving the sovereignty of Kush, particularly during its conflicts with Rome and other foreign powers.

The Meroitic Culture: Architecture, Religion, and Society

Kushite culture was a fusion of indigenous African traditions and external influences, particularly from Egypt and Greece. While Meroe’s architecture—exemplified by its pyramids, temples, and palaces—reflected Egyptian design principles, it also showcased unique innovations in art, sculpture, and city planning. The Meroitic language, written in both hieroglyphics and cursive script, was a significant cultural achievement, reflecting the intellectual vibrancy of the civilization.

Religiously, the Kushites followed a polytheistic belief system, with deities like Amun, Isis, and Apedemak central to their spiritual life. The worship of these gods was expressed through monumental temples, offering chapels, and elaborate funerary rituals. The Meroitic cult of the dead, depicted in the paintings and carvings inside the pyramids, was an essential aspect of Kushite life, underscoring their belief in immortality and the divine protection of their kings and queens.

The Decline of the Kingdom: The Fall of Meroe

The decline of the Kingdom of Kush was gradual and multifaceted. Internal struggles, external invasions, and the rise of rival powers like the Aksumite Empire in Ethiopia contributed to the fall of Meroe. By the 4th century AD, the kingdom’s economic power had waned, and the once-prosperous cities of Meroe, Napata, and Jebel Barkal were abandoned. The last known pyramid, built by Queen Amanipilade in the middle of the 4th century, marks the end of an era for Kush.

Archaeological Rediscovery: Uncovering Kush’s Forgotten Glory

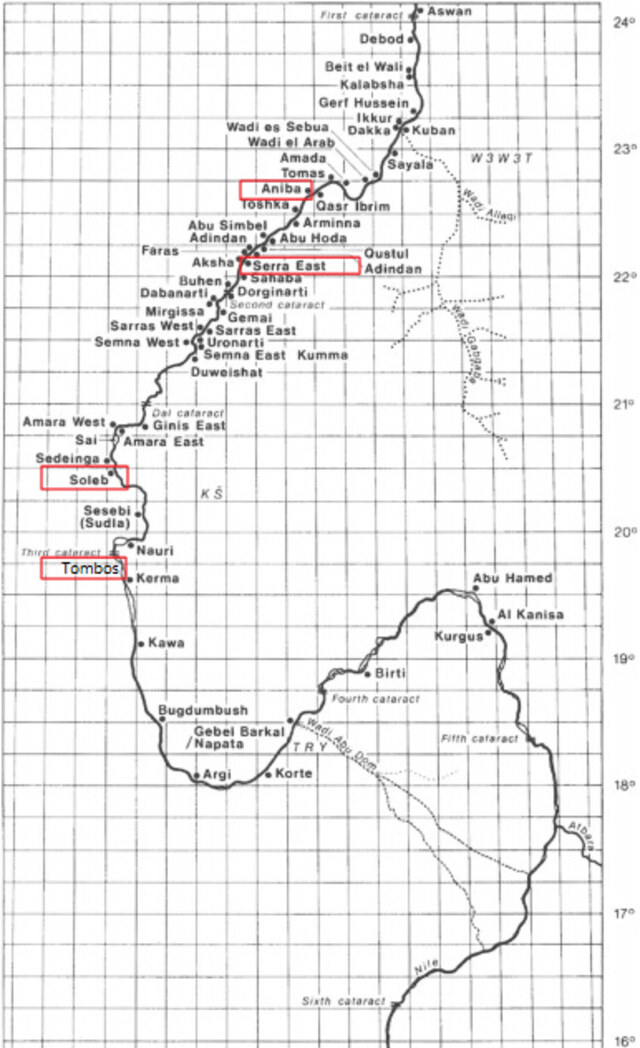

For centuries, the Kingdom of Kush was overlooked in favor of its more famous neighbor, Egypt. But over the past century, archaeologists have worked tirelessly to uncover the secrets of this forgotten empire. Excavations at Meroe and other Kushite sites have revealed a wealth of artifacts, inscriptions, and architectural wonders, shedding light on a civilization that once rivaled Egypt in its glory.

The work of archaeologists like Charles Bonnet has been pivotal in reshaping our understanding of Kush. Bonnet’s excavations at Kerma and Dukki Gel have uncovered evidence of Kush’s early power and its interactions with Egypt. Today, Sudan’s ancient history is experiencing a renaissance, with Meroe’s pyramids and other Kushite sites now drawing the attention of scholars, tourists, and history enthusiasts from around the world.

Kush’s Enduring Legacy: Connecting the Past with the Present

The rediscovery of Kush’s rich cultural heritage has sparked a newfound sense of national pride in Sudan. In recent years, many Sudanese people have begun to look to their ancient past to forge a stronger identity and sense of purpose. The pyramids of Meroe, once buried beneath centuries of neglect, now stand as symbols of a resilient and powerful civilization that played a crucial role in the history of Africa.

As modern Sudan grapples with political and social changes, the legacy of Kush continues to inspire pride and a deeper connection to the country’s ancient roots. For the people of Sudan, the history of Kush is no longer a forgotten chapter; it is a vital part of their cultural heritage that shapes their identity and their future.

Gallery of Kushite Heritage and Meroitic Pyramids

Explore a selection of captivating images showcasing the grandeur of Kushite monuments and the remarkable Meroitic pyramids, offering a glimpse into the rich history and architecture of this ancient civilization.

Video

Watch the video “The Black Pharaohs: The Kingdoms of Kush – The Great Civilizations of the Past” to explore this remarkable ancient civilization.

Conclusion: Rediscovering a Glorious Past

The Kingdom of Kush, with its magnificent pyramids, powerful queens, and rich cultural traditions, offers a compelling narrative of African civilization. The rediscovery of Kush’s ancient cities and tombs has not only unveiled a forgotten empire but has also reshaped our understanding of African history. Today, as Sudan embraces its rich cultural heritage, the Kingdom of Kush stands as a testament to the enduring strength and influence of African civilizations on the world stage.