Throughout history, the treatment of mental illness has often crossed the line between the scientific and the surreal. One such example lies in the “Stone of Folly,” a bizarre and striking motif seen in artwork from the 16th to the 18th centuries. This concept depicted the removal of a literal “stone” from a patient’s head, believed to cure madness or folly. While absurd by today’s standards, these images hold a powerful glimpse into the minds of early physicians and the cultural understanding of mental health. Delving into this captivating theme, we uncover how medicine, metaphor, and magic intertwined in a world that sought to cure what it could not understand.

Hieronymus Bosch and the Origins of the “Stone of Folly”

The concept of the “Stone of Folly” first became widely known through the works of the Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch. His painting, Extracting the Stone of Madness (c.1494–1516), is one of the earliest and most influential depictions of this idea. In Bosch’s surreal scene, a doctor performs a crude surgical procedure to remove a “stone” from a patient’s head, symbolizing the cure for madness. The stone itself is portrayed as a physical object, but its real meaning transcends the literal. It represents the metaphorical belief that mental illness could be removed through physical intervention.

Bosch’s work left a lasting mark on later artists, and the “Stone of Folly” became a recurring motif, drawing attention not only to the medical theories of the time but also to the social perceptions of those suffering from mental health disorders. In many ways, Bosch’s artwork transcended the purely medical and entered the realm of the symbolic, where the “stone” was both a real object and a metaphor for the need to “cure” individuals deemed to be out of touch with societal norms.

Video

Check out the video on “Extracting the Stone of Madness” by Hieronymus Bosch – it’s a fascinating exploration of his iconic work!

The Influence of Jan van Hemessen and Other Artists

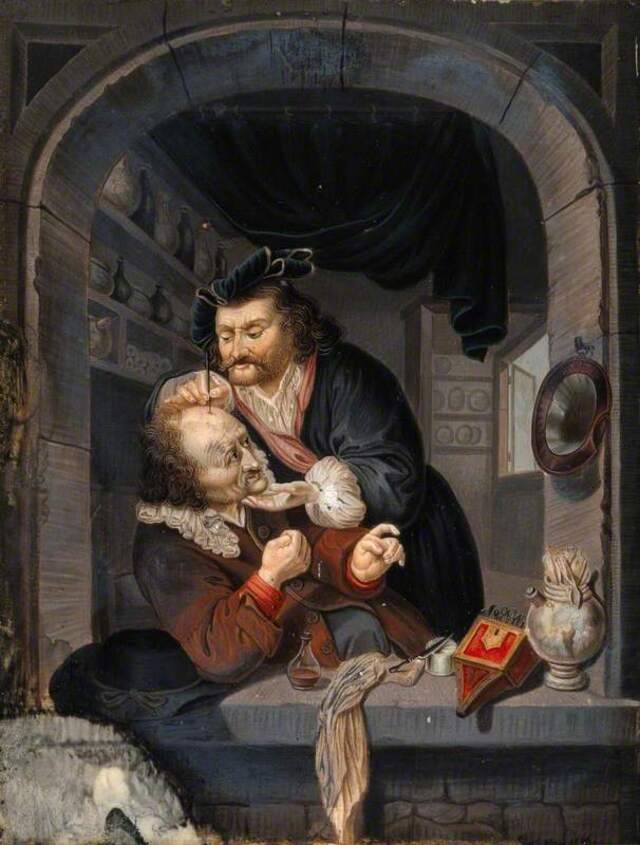

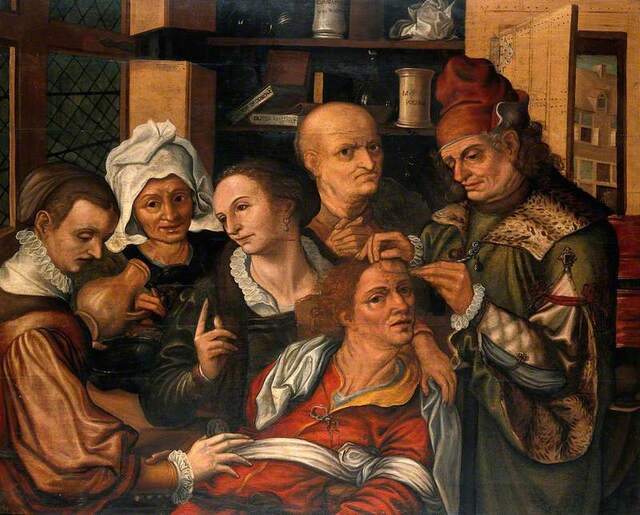

Following Bosch, other artists such as Jan van Hemessen began exploring the “Stone of Folly” motif, further developing its symbolic significance. Hemessen’s painting An Operation for Stone in the Head (c.1500–c.1575) presents a much more graphic depiction of the operation, where a stone is visibly protruding from the patient’s forehead. Unlike Bosch, who left the stone more metaphorical, Hemessen offers a more literal interpretation of the idea, capturing the grotesque and disturbing nature of the procedure.

The visible stone in Hemessen’s painting not only deepens the connection between madness and the body but also introduces the question of whether such a procedure was genuinely believed to work or if it was merely a commentary on the absurdity of trying to treat mental illness with surgical means. The idea of removing a stone from the head, much like a physical illness, challenges our modern understanding of how mental health was once perceived and treated.

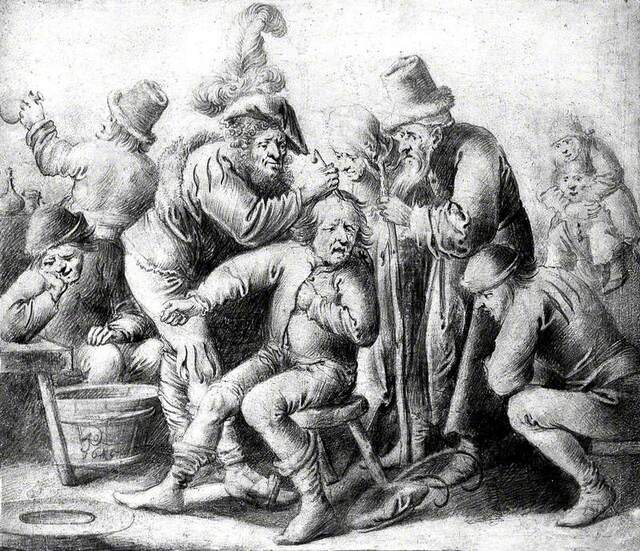

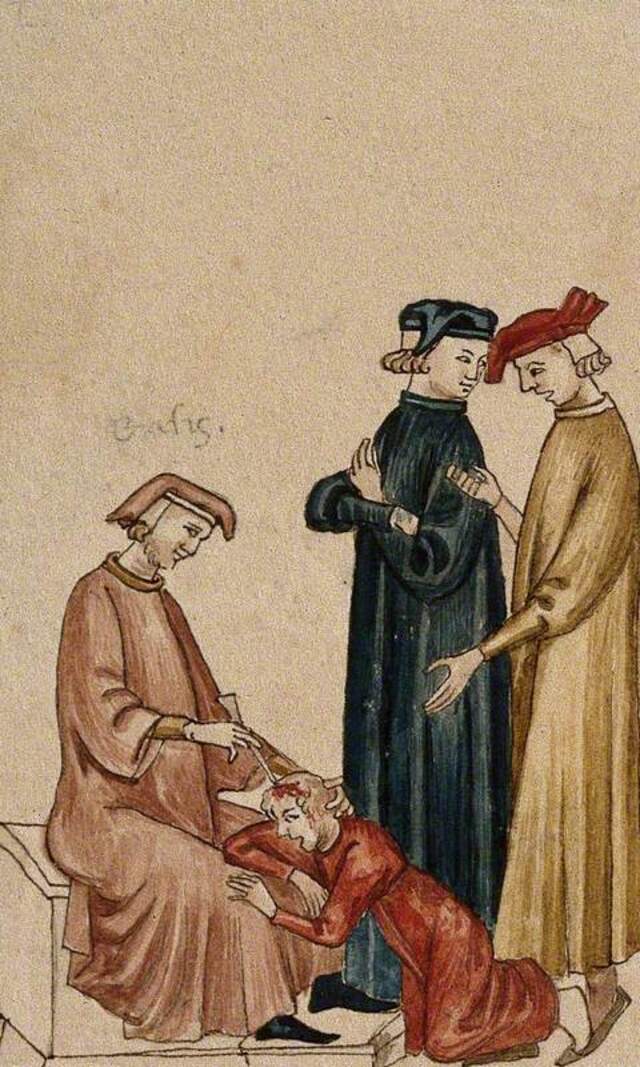

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, numerous other artists took inspiration from these early works, creating variations on the “Stone of Folly.” These paintings were often deeply satirical, using the grotesque imagery of a doctor extracting a stone to comment on the ignorance of both the patients and the physicians involved. Some paintings, like A Sitting Physician Is Trepanning Another Man’s Head, served as dark humor, while others depicted the operation as a form of social commentary on the mistreatment of those suffering from mental illness.

Trepanation and the Early Roots of Surgical Practices

While the “Stone of Folly” was largely a symbolic concept in art, its roots can be traced back to actual medical practices like trepanation. Trepanation, the practice of drilling or scraping a hole into the skull, dates back thousands of years, with evidence found in prehistoric and ancient cultures worldwide. Archaeological discoveries, such as a Bronze Age skull from Jericho showing multiple holes made by this procedure, suggest that early humans believed this practice could cure both physical and mental afflictions.

Whether for spiritual reasons, as a form of medical intervention, or a combination of both, the early practice of trepanation represents the blurred line between the mystical and the medical. In societies where the magical and the medicinal were often intertwined, trepanation may have been viewed not only as a physical treatment but as a ritualistic way to release the “evil spirits” or negative forces believed to be causing illness. The imagery of the “Stone of Folly” might have symbolized this ancient belief, transforming it into a more visual metaphor for both the medical and magical approaches to health.

Symbolism Behind the “Stone of Folly” in 17th and 18th Century Art

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the “Stone of Folly” continued to evolve as both an artistic and medical symbol. These paintings, often satirical in nature, commented on the absurdity of the medical treatments available during the time. For example, in A Surgeon Extracting the Stone of Folly (c.1561), the scene shows a surgeon about to remove the stone, with onlookers—who may or may not understand the true nature of the procedure—gazing eagerly at the operation.

These works suggest that the “stone” could represent more than just a physical object. It could symbolize the irrational and the illogical aspects of human nature, which physicians were expected to cure. In some works, the doctor himself is depicted as the fool, either unaware of the futility of the procedure or perhaps exploiting the belief in the stone for personal gain.

The presence of symbolic elements, such as jars labeled with “conserve of wasps”—a metaphor for lust or irrational desires—further complicates the meaning of the “Stone of Folly.” These items in the background suggest that folly and madness were seen as a combination of physical ailment and moral failing, further reflecting the complex social views of the time regarding mental illness.

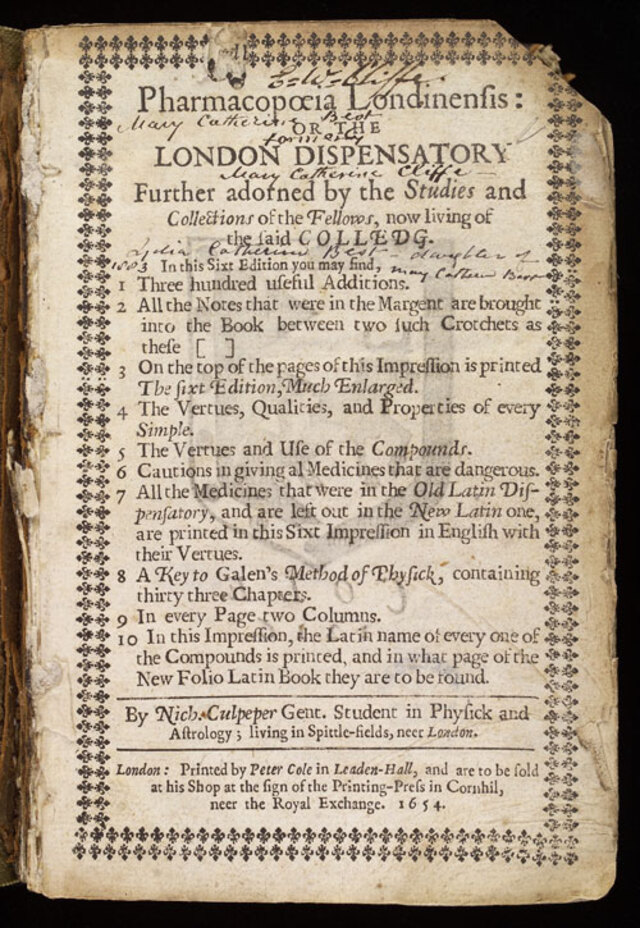

Nicholas Culpeper and the Evolution of Medical Treatment

By the 17th century, medical practices were evolving, with herbal remedies gaining greater prominence in the treatment of various ailments. One of the most influential figures in this period was Nicholas Culpeper, an English herbalist who advocated for the use of natural remedies to treat diseases. In his Pharmacopoeia Londinensis (1649), Culpeper presented a collection of medicinal herbs, some of which are still used in modern treatments. His works played a key role in shifting medical practices away from purely surgical approaches to those that incorporated more holistic and herbal remedies.

While Culpeper’s work focused on remedies based on plants and herbs, his ideas are still tied to the concept of the “Stone of Folly.” The symbolism in the paintings of the time—of extracting the stone as a metaphor for curing folly or madness—began to align with Culpeper’s belief in natural cures. His approach to treating mental illness involved the use of herbs like valerian and lavender, which are still known today for their calming properties. Culpeper’s works represented a growing movement towards understanding mental health through the lens of natural remedies rather than invasive and brutal treatments.

Cultural Context of Folly and Madness in Early Modern Europe

The “Stone of Folly” motif also reflects the cultural context of early modern Europe, where mental illness was often misunderstood and shrouded in superstition. People suffering from conditions like depression, anxiety, and psychosis were frequently labeled as “mad” or “foolish” and subjected to harsh treatments. These treatments, such as trepanation, were seen as attempts to rid the individual of “demons” or “bad humors,” illustrating the extent to which medieval and Renaissance societies sought physical cures for mental afflictions.

This era’s perception of mental illness was influenced by both religious beliefs and emerging medical theories. The concept of curing folly through the removal of a stone reflects a dual belief in the importance of both physical and moral interventions in healing. At a time when societal norms were strict and nonconformity was often equated with madness, such imagery served to reinforce the idea that mental illness was something that could be excised or eradicated from the body, just like a physical ailment.

Conclusion: Magic, Madness, and the Enduring Symbolism of the “Stone of Folly”

The “Stone of Folly” remains a powerful symbol of the complex relationship between madness, medicine, and metaphor in early modern Europe. From Bosch’s eerie depictions to the herbal remedies of Nicholas Culpeper, this motif reveals much about the evolving understanding of mental health and the treatments of the time.

While we now recognize mental illness as a complex and multifaceted condition, the art and medical practices of the past provide valuable insights into how society once viewed and dealt with mental suffering. Whether through the literal or symbolic removal of the stone, these paintings continue to resonate with us today, reminding us of the fine line between magic and madness, cure and cruelty, and the ever-changing understanding of the human mind.

Video

Watch the video on medieval medicine in this animated history series – it’s a quick and engaging look at healthcare from the past!