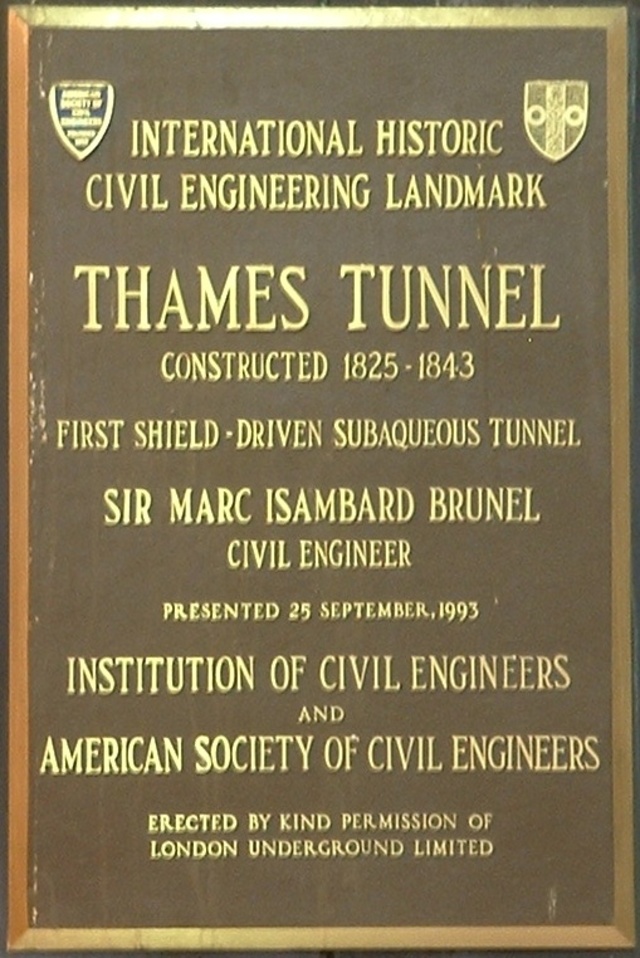

The Thames Tunnel, a pioneering feat of civil engineering, stands as a testament to the perseverance and ingenuity of its creators. Stretching beneath the River Thames in London, this tunnel became the first successful attempt to tunnel under a navigable river, forever changing the course of transportation and urban development. From its troubled beginnings to its eventual transformation into a vital part of London’s transport infrastructure, the story of the Thames Tunnel is one of challenges, innovation, and triumph.

The Early Challenges: Predecessors and Failures

The idea of tunneling beneath the Thames was far from new. By the early 19th century, London was facing significant congestion, particularly in the port areas where the city’s commercial activity was concentrated. While London Bridge had been the city’s main crossing point, its cramped structure proved insufficient to meet the growing demands of the expanding city. The possibility of a tunnel under the river was proposed, but previous attempts had failed.

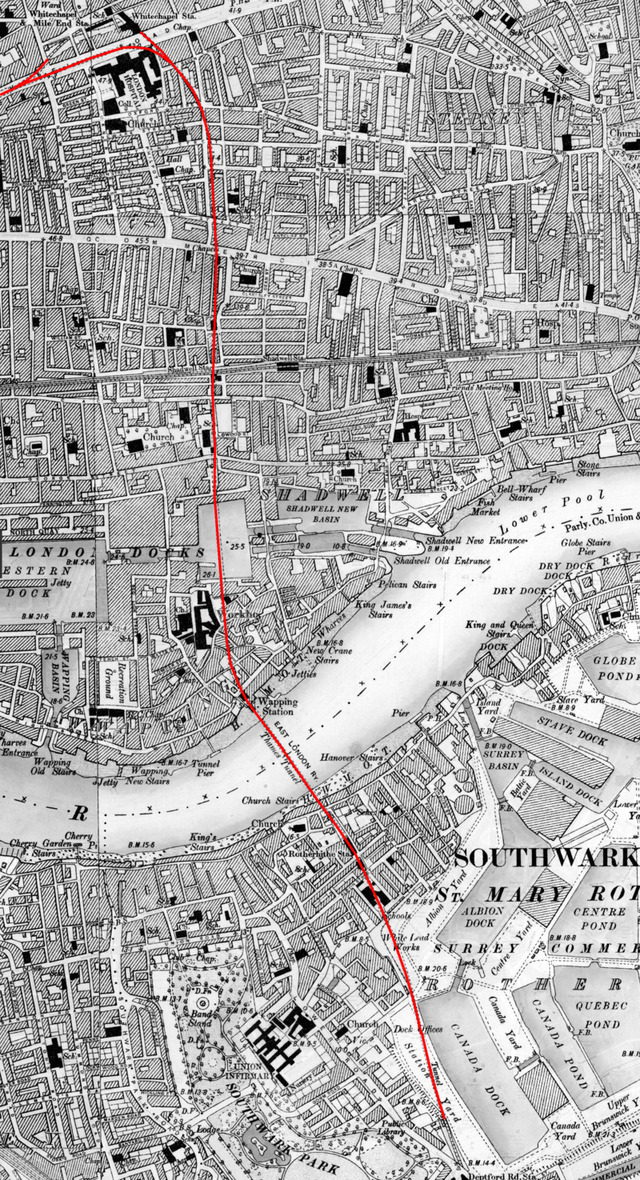

One such attempt was the Thames Archway project, led by the Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick. In 1807, Trevithick and his team tried to dig a tunnel beneath the river from Rotherhithe to Wapping, but they faced insurmountable problems with the soft, waterlogged ground. Water quickly flooded their tunnel, and the ambitious project was abandoned. The failures of these early ventures left engineers and the public skeptical about the feasibility of tunneling under a major river.

Video

Check out this video to explore the fascinating history of the Thames Tunnel, uncovering the engineering marvel that transformed London’s transportation system.

Marc Brunel’s Vision and Innovation

Despite these failures, one man refused to give up on the idea: Marc Brunel. A French-born engineer who had made his mark with several significant inventions, Brunel was determined to find a way to build a tunnel beneath the Thames. After witnessing the shortcomings of the previous attempts, he envisioned a new approach—a tunneling shield that would provide structural support to the tunnel as it was being dug.

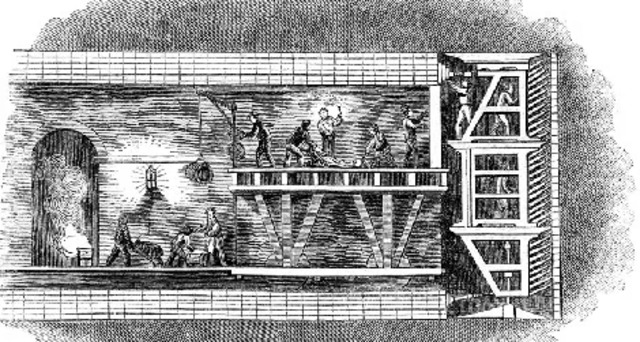

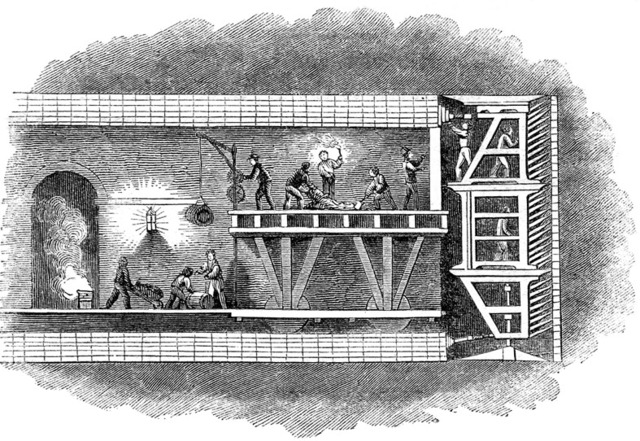

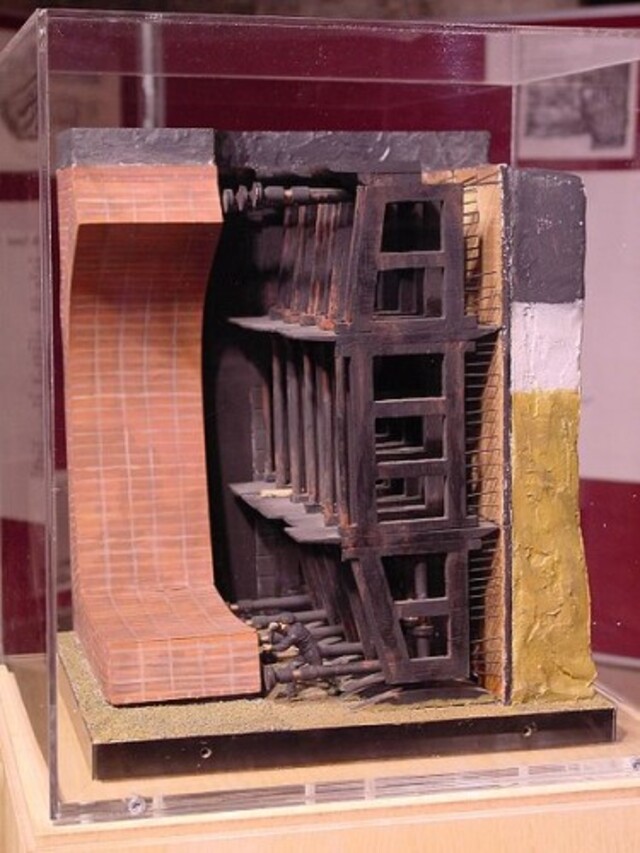

Brunel’s tunneling shield, patented in 1818, was a groundbreaking invention that would change tunneling technology forever. The shield was a massive iron frame divided into several compartments, with each compartment holding one worker who would excavate the earth in front of them. As the work progressed, the shield would slowly advance, protecting the workers from the risk of collapse and flooding. This innovation proved to be the key to the Thames Tunnel’s success.

The Construction Process: Innovation Meets Adversity

Work on the Thames Tunnel began in 1825, but it was far from smooth sailing. The project faced numerous setbacks, not least of which was the hazardous working conditions. Workers toiled in cramped, poorly ventilated spaces, and many fell ill from exposure to contaminated river water and methane gas. Despite these challenges, the tunnel continued to inch forward, and the tunneling shield proved to be an effective tool in holding back the surrounding earth.

However, the tunnel’s path under the river was not without its difficulties. The workers encountered various layers of soft clay, gravel, and quicksand, making excavation slow and unpredictable. At one point, a massive flood inundated the tunnel, forcing workers to abandon their efforts and pump the water out. After months of painstaking repairs, work resumed, but the tunnel was soon struck by another flood, causing further delays.

Throughout these hardships, Marc Brunel’s son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, emerged as a key figure in the project. Taking over when the resident engineer fell ill, Isambard’s leadership and engineering prowess were instrumental in pushing the tunnel closer to completion.

Notable Figures and Contributions

Marc Brunel’s persistence was matched only by his son’s brilliance. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, though young at the time, proved himself to be an extraordinary engineer, later known for his work on the Great Western Railway and the Clifton Suspension Bridge. Isambard took over the Thames Tunnel project in 1826 after his father fell ill. His leadership during the critical years of the project ensured that the tunnel remained on track.

Isambard’s own innovations, including the development of a stronger tunneling shield and the use of a diving bell to seal breaches in the tunnel, contributed significantly to the eventual success of the project. His ability to solve problems in real-time, often under extreme pressure, cemented his reputation as one of the greatest engineers of the 19th century.

Completion and Public Reception

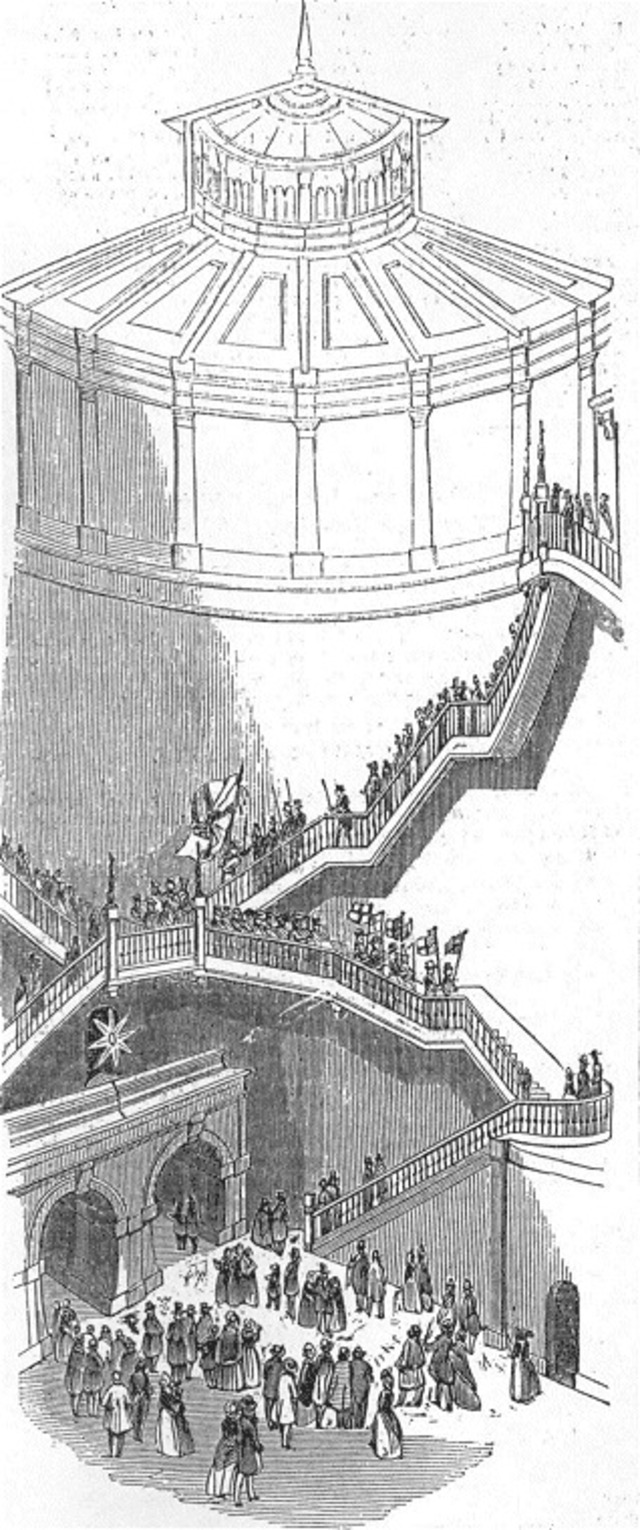

After nearly two decades of work and a host of challenges, the Thames Tunnel was finally completed in 1841. Despite its technical success, the tunnel was not an immediate financial triumph. Initially designed to accommodate horse-drawn carriages, it was instead used primarily by pedestrians. The tunnel became a popular tourist attraction, with up to two million visitors annually paying a penny to walk through its dark, narrow passages.

The Thames Tunnel was a symbol of Victorian engineering achievement, but its financial failure highlighted the limitations of the original design. While the public marveled at the tunnel’s construction, the project did not generate enough revenue to cover its expenses.

Transition to Railway Use

In the mid-19th century, the advent of the railway brought new life to the Thames Tunnel. In 1865, the East London Railway Company purchased the tunnel for £800,000 with the intention of using it for rail transport. The tunnel’s original design, with its generous headroom, proved ideal for trains, and the first trains ran through the tunnel in 1869.

By the late 19th century, the tunnel had become an integral part of London’s transport network. It was eventually absorbed into the London Underground system, where it remained in operation for much of the 20th century. Today, it is part of the London Overground network and continues to serve as a vital connection between the northern and southern banks of the Thames.

Legacy and Modern Influence

The construction of the Thames Tunnel had a lasting impact on civil engineering. It demonstrated that tunneling beneath navigable rivers was not only possible but could be achieved with the right combination of technology and perseverance. The tunnel inspired the construction of several other underwater tunnels in the UK and around the world, including the Severn Tunnel and the Mersey Railway Tunnel.

In recognition of its importance, the Thames Tunnel was designated as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1991. In 1995, it was listed as Grade II*, acknowledging its architectural and historical significance.

Visiting the Thames Tunnel Today

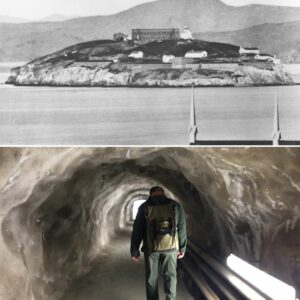

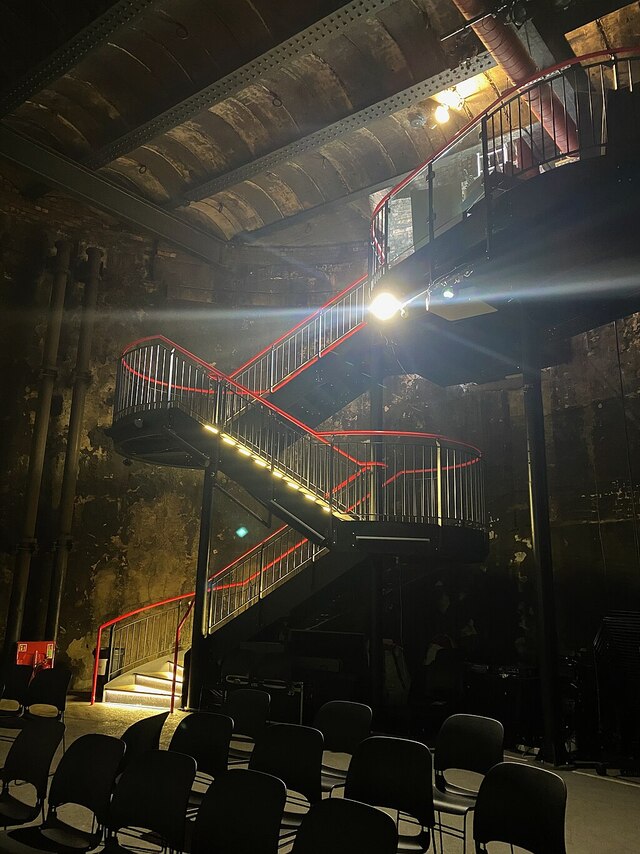

Today, the Thames Tunnel is a cherished part of London’s history. The Brunel Museum, located at the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel, offers visitors a chance to learn about the tunnel’s construction and its enduring legacy. The museum is housed in the original engine house that was used to pump out the tunnel during its construction, and it provides a fascinating glimpse into the challenges faced by the engineers who built the tunnel.

For those interested in the tunnel itself, tours are available that explore its historic significance and its transformation from a failed tourist attraction to a crucial part of London’s transport infrastructure.

Video

Tune into this video from BBC News to get rare access to the “eighth wonder of the world,” offering a unique look at this incredible site and its significance.

Conclusion

The Thames Tunnel is more than just a tunnel; it is a symbol of human ingenuity and determination. From its humble beginnings as a failed project to its eventual transformation into a vital transport link, the tunnel’s story is a reminder of the power of perseverance in the face of adversity. Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s contributions to the project continue to influence civil engineering practices today, making the Thames Tunnel one of the most significant engineering achievements of the 19th century.