Beneath the surface of Australia’s colonial history lies a hidden narrative, one that reveals how women in 19th-century institutions quietly defied the constraints of their environment. At Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks, once a notorious site for convicts, an archaeological discovery unearthed the surprising foodstuffs secretly buried beneath the floorboards. These clandestine meals, far from the monotonous diet dictated by the authorities, tell a story of resistance, individuality, and the complex cultural interactions that took place in this harsh colonial setting.

Introduction to Hyde Park Barracks and Its Historical Significance

Hyde Park Barracks, constructed between 1817 and 1819, was originally designed to house male convicts in New South Wales. Following the end of convict transportation in the mid-1800s, the barracks was repurposed as a Female Immigration Depot, providing housing and support for single migrant women between 1848 and 1887, as well as a refuge for those unable to support themselves due to illness, age, or disability.

Over time, it became a site that embodied the struggles of these women, where their lives were strictly controlled and where their diets, according to official records, were drab and monotonous, consisting mainly of bread, meat, and tea. This bleak portrayal, however, fails to capture the complexities of life within the barracks.

Video

Tune into this video to uncover hidden foodstuffs discovered beneath a 19th-century Australian colonial institution, revealing intriguing historical insights.

The Role of Food in Colonial Institutions

In the 19th century, colonial institutions played a crucial role in maintaining order and control, and one of the ways they achieved this was through the regulation of food. Meals were standardized, with rations of bread, meat, and tea being common fare in institutions like the Hyde Park Barracks. Food was not just a means of sustenance but a tool for enforcing discipline and creating social hierarchies. Official records often painted a dull picture of institutional diets, highlighting their blandness and the idealized British diet that was expected of the immigrants.

However, the historical narrative of bland food has been challenged by recent archaeological findings, which paint a vastly different picture. These discoveries show that the women at the barracks were not limited to the bland rations prescribed to them. Instead, they managed to procure a wide variety of foods, including fruits, vegetables, spices, and even nuts that were not recorded in any official records.

Unveiling Hidden Foodstuffs Beneath the Floorboards

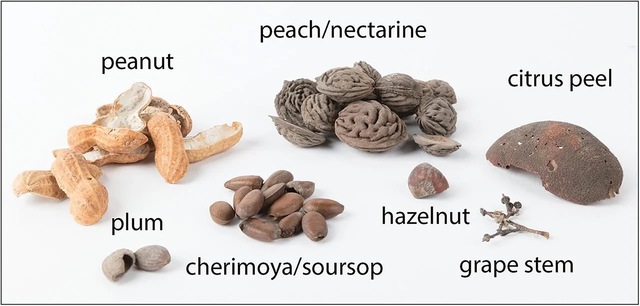

The discovery of foodstuffs hidden under the floorboards of the Hyde Park Barracks during excavations in the early 1980s was a groundbreaking moment in understanding the daily lives of the women who lived there. While the official records described their diet as simple and monotonous, the hidden foodstuffs found beneath the floors revealed a different story. The plant remains, including macadamia nuts, quandong fruit, American corn cobs, lychees, and citrus peel, indicated that the women had access to a variety of food items that were never part of the official rations.

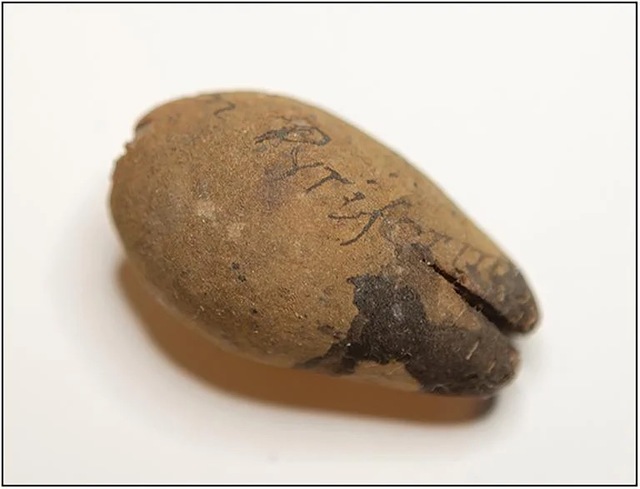

These foods, many of which were likely procured informally, suggest that the women were not entirely passive recipients of the institutional diet. Instead, they found ways to acquire food outside the system, perhaps by bartering, visiting local markets, or receiving provisions during trips to church. The act of hiding these foods under the floorboards shows a deliberate attempt to keep them hidden from the institutional authorities, offering a glimpse into the subtle ways in which the women resisted the rigid control imposed on them.

The Soggy Truth: Australian Native and Imported Foods

The plant remains found beneath the Hyde Park Barracks were not limited to local Australian flora; they also included a mix of imported foods that reflected the global nature of trade during the colonial period. Among the finds were native Australian foods such as macadamia nuts and quandong fruit, as well as foods introduced from around the world, including American corn, Southeast Asian lychees, and European citrus fruits.

The presence of these diverse foodstuffs highlights the global nature of trade during the 19th century and the ways in which different cultures and foods intersected in colonial Australia. The inclusion of native Australian plants, such as the bottlebrush and tea tree, suggests that the women were not only reliant on imported foods but were also developing a connection to the land they inhabited.

Acts of Resistance: How Women Used Food to Retain Individuality

The act of concealing food beneath the floorboards was more than just a practical response to hunger—it was a small but significant form of resistance. In an environment where personal freedom was severely restricted, food became a means of asserting individuality and maintaining a sense of autonomy. The women’s ability to procure and consume food outside of the official system was a quiet act of defiance against the institutional control that sought to homogenize their lives.

As Dr. Kimberley Connor, a leading researcher on the subject, explains, the act of sharing food like peanuts or sneaking an orange into the dormitory allowed the women to hold onto their sense of self and their relationships in an environment that otherwise sought to suppress both. These small acts of rebellion may have been a way for the women to resist the uniformity imposed on them, helping them maintain their cultural identity and personal bonds despite the harsh conditions of the institution.

Global and Local Influence: The Exchange of Foodstuffs in Colonial Australia

The discovery of a wide range of foodstuffs from different parts of the world in the Hyde Park Barracks underscores the extent of global trade during the 19th century. From Southeast Asia to the Americas, foodstuffs like lychees, Brazil nuts, and maize were introduced to Australia through colonial trade routes. These foods were not just traded for economic purposes—they also became part of the cultural exchange between different peoples, reflecting the multicultural nature of colonial Australia.

In addition to foreign imports, the women’s consumption of native Australian foods suggests that they were also beginning to adapt to their new environment. The presence of native plants like the woody pear (Xylomelum pyriforme) highlights their growing interest in the local flora and their efforts to incorporate local resources into their daily lives.

Archaeology and Its Role in Reconstructing Hidden Histories

The findings at Hyde Park Barracks underscore the importance of archaeology in uncovering the hidden stories of the past. While official records provide valuable insights into the broader historical context, they often fail to capture the lived experiences of individuals. Archaeological discoveries, such as the hidden foodstuffs, offer a more nuanced understanding of life in colonial institutions.

By analyzing the plant remains found at the barracks, researchers have been able to reconstruct a more accurate picture of the women’s daily lives. These discoveries not only shed light on their diet but also provide evidence of how they interacted with the wider colonial world. As Dr. Connor notes, archaeology can reveal secrets that written history cannot, offering a more complete understanding of the past.

Video

Watch this video to learn fun facts about Australia’s unique culture, highlighting its traditions, history, and the things that make it truly special.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Forgotten Voices in Australian History

The hidden foodstuffs found beneath the floorboards of the Hyde Park Barracks offer a fascinating glimpse into the lives of the women who lived there. These discoveries challenge the official narrative of monotonous diets and highlight the ways in which the women resisted the oppressive conditions of colonial institutions. Through these small acts of rebellion, the women were able to maintain their individuality and cultural identity, providing a powerful reminder of the resilience of the human spirit.

As archaeological research continues, these discoveries remind us of the importance of integrating archaeological evidence with historical records to gain a fuller understanding of the past. By uncovering the hidden stories of those who lived in colonial institutions, we can begin to reclaim forgotten voices and shed light on the complexities of life in 19th-century Australia.